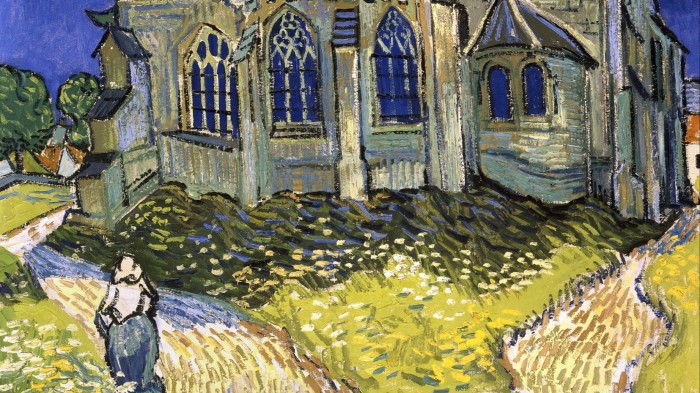

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Stay informed with free updatesSimply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.This past week the “bourdon” bell of the newly restored Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris rang for the first time in five years. The ringing of the bell, which was cast in 1683, signalled the start of an evening of events celebrating Notre-Dame’s reopening after the devastating fire of 2019. The sound of bells seemed to be a call to the city, and perhaps even the world at large, given all the political divisions, to refocus on spiritual and social renewal. I watched part of the event as it streamed live on the BBC. It made me think about how rare it is these days for church bells to draw anyone’s attention, let alone an entire global audience. When Paris Archbishop Laurent Ulrich knocked three times on the doors of Notre-Dame, he addressed the church itself with the words, “Open your doors to help us to seek love and truth, justice and peace”. The bells seemed symbolic of an invitation for us to interrupt our lives not just to watch this event but perhaps also to consider the pursuit of “love, truth, justice and peace”, however we choose to do so. Given the structure of modern daily life how many of us today would stop whatever we were doing for ringing church bells? But perhaps some of the things we dismiss as interruptions might in fact be opportunities to reflect on other aspects of our lives, or even just to calm our hurried pace.In June 1890, just a month before he died, Vincent van Gogh painted “The Church at Auvers”, which is now housed at the Musée d’Orsay. The painting shows a large grey-toned Gothic-style church standing against a brilliant cobalt blue sky; the church windows are also a vivid blue but the building itself seems daunting, empty of its own vibrancy, even purpose, perhaps. The surrounding lawn is bright green, dotted with white flowers, one end caught in sunlight. A diverging path leads towards the building and a lone figure walks on the left pathway towards it. What do we deem sacred enough to interrupt our own days?The painting is both beautiful and haunting to me. The church was built in the 12th century, and still stands in Auvers-sur-Oise, in the outskirts of Paris, and one wonders how many times its bells have rung over the centuries. In earlier days, church bells served so many purposes in communities. They kept time, they signalled when to stop and rest or have meals, and, naturally, they also rang before services throughout the day. In previous centuries, people would likely have recognised ringing church bells as a useful and necessary part of their daily lives. Bells were less a disturbance and more an invitation to pay attention to our activity during the day, stopping and starting our work for other activities. I imagine many of us who live or work in the vicinity of ringing church bells might find the bells at best, a charming remnant of history; at worst, a noisy distraction. But I do wonder what might be different about our days if we were used to being prompted to attend to the seemingly less productive parts of our lives. Would it change our disposition towards interruptions in general, maybe making us more open to experiencing things both unexpected and life-affirming? In the 1870 painting “The Pet Goldfinch” by French painter Henriette Browne (whose birth name was Sophie Boutellier), a young girl sits at a desk with an ink bottle and stacks of books. She holds a quill in her hand as she pauses from writing on a loose sheet of paper to stare at the little goldfinch. The bird is perched on the edge of the table, and we can just make out the black and yellow of its wings and its little red face. The bird’s cage hangs on the wall with its door open. I like this work because it reminds me how easily children permit interruptions in their daily life, and how they seem to have a natural understanding that some of these intrusions can be invitations to wonder, even when they come in the middle of necessary responsibilities. As the little bird, poised and present for the child’s gaze, reminds us, interruptions can call us to see another element of life, or to focus our attention on new ideas, creative possibilities and possibly even new relationships. I wonder if we might feel more fulfilled if our own agendas were not so rigid and inflexible to wonder. There is so much going on in British artist Grayson Perry’s 2012 tapestry “The Annunciation of the Virgin Deal”. This work is the fourth tapestry in a series called The Vanity of Small Differences that takes its inspiration from William Hogarth’s 1730s satirical series A Rake’s Progress, which tells the story of a British heir named Tom Rakewell who spends all his money and eventually ends up in “The Madhouse”. Perry’s tapestries follow the economic rise and decline of a character called Tim Rakewell and use religious imagery as part of a satirical approach that seems to lampoon the pursuit of a bourgeois lifestyle. This woven tableau is filled with objects that serve as material signifiers of rising social status. The protagonist Rakewell sits on a couch holding his baby next to a lapdog and a pillow that says “Bourgeois and Proud”. On the wall behind are framed portraits of Bill Gates and Steve Jobs, symbolic of modern wealth and power. His wife leans against a stove range where a blue Le Creuset pan sits. On the kitchen table is an electronic notebook showing an FT news story about the fictitious Rakewell’s multimillion-pound deal with Virgin. I love how the person announcing the deal to the assembled characters in the room is depicted as an angel bearing the ultimate good news. This figure, positioned centrally on the canvas, is an older woman with white hair and wings. Perry is here playing on the long tradition of Annunciation scenes in art history, the depictions of the biblical story of the angel Gabriel interrupting Mary’s day to declare that she has been chosen to bear the divine saviour, to make a point about the almost religious devotion to wealth accumulation in modern secular societies. It does make me wonder if, given the option, we too would look for a seat in this tapestry. In a world centred on material success we need to be all the more alert to the interruptions in our lives, those that tempt us further along this path, and those that offer us the opportunity to reflect on our relationships with others, with nature, and possibly even with spirituality. What do we deem sacred enough to interrupt our own days? Because life rarely consults us ahead of new developments and opportunities. What proverbial bells are ringing and calling us to attention in the midst of our busy day?Enuma Okoro is a New York-based writer for FT Life & Arts enuma.okoro@ft.comFind out about our latest stories first — follow FTWeekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen

rewrite this title in Arabic When church bells stop us in our tracks

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 خليجي 247. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.