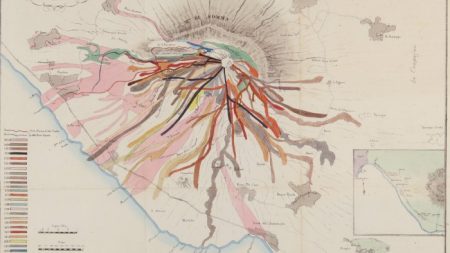

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic “Introduced today to the man who beyond all doubt is the greatest of the age; greatest in every faculty of the imagination, in every branch of scenic knowledge, at once the painter and poet of the day.” So wrote 21-year-old John Ruskin on meeting Turner in 1840. Recognising Turner as so innovative, different from any painter before, that he demanded a new sort of writing about art, Ruskin championed his hero across five volumes in Modern Painters. In rich, allusive prose evocative of the artist’s spectacular atmospheric effects, he declared that by “truth of tone” and “truth of colour” Turner conveyed a truth deeper, in imaginative expression, than the most accomplished naturalism. This was the future of modern painting: subjective, visionary, sensational.Turner’s 250th birthday is celebrated in 2025, and still he enthrals. His paintings have become part of British national identity, passing from art to popular culture. In the 2012 movie Skyfall, James Bond and Q meet in front of “The Fighting Temeraire”, the magnificent ghostly sailing ship about to be broken up for scrap, redundant in the age of steam, embodied in the squat, spewing black tug. The sunset picture, sweeping from flame bright to dark, symbolises Bond’s age and the turning tide of the British intelligence service. For us all, it suggests the journey through life. During lockdown, the “Temeraire” and “Rain, Steam, and Speed”, the train hurtling towards abstraction in a blur of swirling, sprayed paint, featured in the National Gallery’s top 10 paintings viewed online — Turner the only artist appearing twice. Why is he so beloved?The immediate answer is that the pictures are deeply pleasurable. As museums tend towards the conceptual and political, Turner guarantees painterly delight. His impact is instant and sensuous, his themes vast and inclusive: man and nature, present versus past, the rise and fall of empires. He engages and immerses. “Make haste,” wrote Thackeray when “Rain, Steam, and Speed” appeared at the Royal Academy, “lest it dash out of the picture, and be away up Charing Cross.”Turner belongs to Romanticism’s disorder. Smashing classical equilibrium, he created pictures for a churning industrialising ageTurner is theatrical, and also ambivalent — so we go on talking about him. His most political painting, “The Slave Ship”, subsumes man’s inhumanity to man into a tempest where, dashed with maimed bodies thrown overboard, a violent lurid ocean “burns like gold, and bathes like blood,” wrote Ruskin. Does Turner aestheticise terror or bring down the power of nature on the unnatural horror of slavery? Was he patriotic or pessimistic about the British empire? Did he embrace progress (the train) or nostalgia (the sailing ship)? In painting, he did both. His idol, 17th-century painter Claude Lorraine, inspired his ambition, monumentality and grandeur. But coming of age during the French Revolution, Turner belongs to romanticism’s disorder. Smashing Claude’s classical equilibrium, he created pictures for a churning industrialising age, uncertain of its relationship with the natural world, thus newly fixated on landscape in painting and poetry — Turner’s peers are Constable (born 1776), Wordsworth (1770) and Coleridge (1772).The roll call of exhibitions celebrating Turner at 250 begins in Britain with Edinburgh’s recently opened Turner in January. The birthday surprise of this popular annual display of watercolours bequeathed by Henry Vaughan, restricted to January when daylight is weakest, is a first-time swap with Dublin’s similarly preserved, pristine watercolours from Vaughan’s legacy there. The turbulent panorama “Edinburgh from below Arthur’s Seat” has come home, among many arrivals and departures. A favourite Turner setting is the port, stirring feelings of home and adventure, beginnings and endings. In the Plymouth storm watercolour “A Ship against the Mewstone”, the sails are almost horizontal on leaping waves, illuminated against thunderous clouds in a shaft of sunlight: can the boat make it back? In “Ostend Harbour”, a lone observer, gazing towards England, watches the tides beneath red-orange skies, shimmering on ivory wove paper.Bath’s Holburne Museum follows with Impressions in Watercolour (May—August). Both shows tell how the medium was far from secondary for Turner; he wanted to capture life “on the wing”, he said, and watercolour encouraged the loose, improvisatory experiments in oil depicting fluid, fleeting moments. The distinctive, delicate films of colour floating on his canvases are close to watercolour effects.Before Turner, painting was static, highly finished and concerned with events from history; he animated it into the present tense. JMW Turner: Romance and Reality is the title of Yale’s 2025 show (March-July). It stars “The Dort”, an intricate yet ethereal delineation of an ordinary daily packet boat under glowing, even light. Constable thought it “the most complete work of genius I ever saw”, recalling its “canal with numerous boats making thousands of beautiful shapes”. The paired paintings Turner bequeathed specifically to hang alongside Lorraine’s at the National Gallery claim everyday life is as significant as historical subjects, that individuals anonymous and heroic are equally shadowed by forces of destiny. “Sun Rising through Vapour” takes place on a casual morning when fishermen unload their catch by a silvery-white sea — but phantom-like warships in the mist are warning notes; this is 1807 in Napoleon’s Europe. In “Dido Building Carthage”, the queen, her architects, builders, merchants, energetically construct the imperial capital whose doom is foretold by her husband’s tomb, and by the pathos of children launching flimsy toy boats. Most of Turner’s bequest to the nation, hundreds of paintings, has since 1987 lived at Tate Britain’s Clore Gallery, reorganised last year into a marvellous, free, nine-room retrospective. It begins with the brooding moonlit “Fisherman at Sea” (1796) — already Turner aged 21 paints everything in motion, tilting, unpredictable. His sea paintings resonated from the start in our island nation. Now they seem to herald environmental crisis: his mighty stagings of man overwhelmed by nature — the vortex of a blizzard “Snow Storm — Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth” — or our impact on it, for example the predatory “Whalers”. The Clore concludes with late landscapes dissolving into light — “Norham Castle, Sunrise”, “Sunrise with Sea Monsters” — accompanied by a brilliant yellow Mark Rothko abstraction. “This man Turner, he learnt a lot from me,” Rothko quipped in 1966. The juxtaposition is a corrective. Tate’s division in 2000, separating British works at Millbank from post-1900 global art at Tate Modern, isolated Turner from the sweep of art history — to which he remains fundamental. His long influence keeps him fresh, sparking constant reappraisal. In Dialogues with Turner: Evoking the Sublime (to May) at Museum of Art Pudong, Shanghai, the world’s most famous watercolour, “The Blue Rigi, Sunrise”, its iridescent morning star shining on scratched white paper, is joined by Olafur Eliasson’s installation “Your Double-Lighthouse Projection” — the sublime across centuries and different media. In 2012, Tate Liverpool’s Turner Monet Twombly drew out Turner’s affinities with impressionism, which he heralded (“we are all descended from the Englishman Turner,” Pissarro admitted), and with Cy Twombly’s semi-abstractions at the turn of the 21st century. Twombly’s inky black “Three Studies from the Temeraire” (1998-99) pays homage to their shared subject of sumptuous ships of death — Turner’s “Peace — Burial at Sea”; his funereal gondolas in “St Benedetto, Looking towards Fusina”. So Turner is both our contemporary and siren voice of 19th-century Britain. Tate Britain’s Turner and Constable (from November) will explore the contrasting approaches of the two landscapists who burst on the scene simultaneously in a country with no previous painting achievements comparable to Italy’s Renaissance, the Dutch golden age or French classicism. Perhaps that is the point — neither were oppressed by tradition, nor, because of the Napoleonic wars, could they make the customary pilgrimage of artistic formation to Italy. When Turner finally reached Italy in 1819, he was over 40, and responded not to its classical tropes (he was a hopeless figure painter) but to its radiant light. From then on, a golden luminosity suffused and heightened his paintings, not only of Italy — though his Venice views, converging shifting watery effects with themes of imperial decline, have a special elegiac beauty. The 19th-century age of materialism and realism, when artists from Constable to Monet insisted they painted their own visual experience, is fascinatingly bracketed by Turner and Van Gogh, who painted what they imagined. Van Gogh’s agitated spirals are descendants of Turner’s spinning vortices — a direct line felt if you go from the National Gallery’s Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers exhibition to the Clore.Both Turner and Van Gogh were northern European artists who found their fullest expression under the Mediterranean sun, unprecedentedly raising the colour key to challenge what painting could be. Dazzling, consoling, beguiling, they brighten the winter and troubled times like rare northern lights.‘Turner in January’ is at the Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, January 1—31; ‘JMW Turner: Romance and Reality’ is at Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut, March 29 — July 27; ‘Dialogues with Turner, Evoking the Sublime’ is at MAP, Shanghai, to May 10; ‘Turner and Constable’ is at Tate Britain, London, November 27 — April 12 2026Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning

rewrite this title in Arabic Turner at 250 — why is he so beloved?

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 خليجي 247. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.