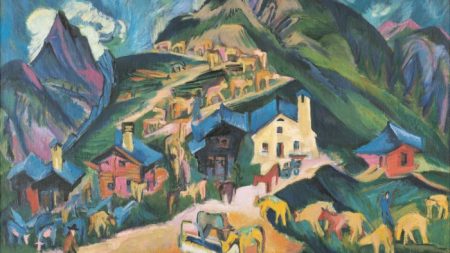

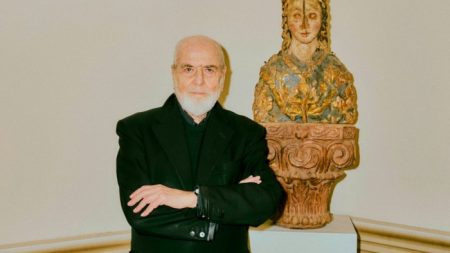

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic When, 12 years ago, the Belgian artist Arne Quinze bought an old stable house in the affluent village of Sint-Martens-Latem near Ghent, one of the first things he did was cut down the hedge that obscured the entrance. Most of the other showcase estates in the village were, and still are, similarly semi-hidden by surrounding greenery. “Without thinking, everyone mindlessly lives in boxes within boxes,” says Quinze. Wearing a T-shirt that reads “Don’t Pet the Bison”, he is sitting on the wooden deck behind his house, which has been built around several large linden trees. The restless, fit 52-year-old, known among many other things for building a massive installation at Burning Man, has just returned from competing in a five-week-long Peking-to-Paris classic car rally. (Up next: a marathon with his daughter, Amber, in the Arctic.)The second thing Quinze did, with the help of an assistant gardener, was to transform the property’s manicured lawn into an untamed field of flowers: purple loosestrife, sky-blue salvia, salmon-pink “Helen Elizabeth” poppies, orange butterfly weed, yellow and orange heleniums, and various wild grasses – a landscape in which the colours and blooms evolve over the seasons like slow-motion fireworks. “Everything is growing at random,” he explains. “I choose the plants – I have planted more than 150,000 of them – and give them space, but at a certain moment I let go of controlling them. It’s always in a state of flux. Every day I am surprised by something.” He looks down at a tree trunk that has been repurposed as a table and points to the tiny buds unfurling from its centre, as excited as a child. “That’s what I try to paint, that journey of getting lost in the beauty of nature,” he says. “You don’t need to go to the Amazon to discover nature. Just go to your garden or to a park and open your eyes.”The old stables that Quinze lives in with his family – he has five children from two former wives – has evolved as colourfully and chaotically as the garden. From the outside it appears small, but inside it’s a labyrinth, spanning three floors and 17,000sq ft – a house of mirrors, every surface covered with pattern and art. In possibly the most radical of his attempts to merge his home with nature, Quinze has allowed it to be almost completely swallowed by vines. He claims it’s an extremely beneficial collaboration. “In the summer my windows disappear and keep the heat out. In the autumn the windows open up and light enters and warms up the house again.” In late June, the head of one of the entrances – there are three – is so heavy with fragrant jasmine that if a visitor is taller than six feet they have to duck to get through.Quinze’s design goals have always been to “create a home that feels like we’re permanently on holiday”. He heads past a pool table to the family lounge and cinema room, a large space anchored by massive rectangular poufs in various sizes, upholstered with different textiles and layered in multicoloured velvet pillows. He points to a side table installed near a window flanked by two wide, soft chairs covered in a wild paisley pattern. “That’s the backgammon table,” he says. “We play backgammon almost every day.” To his mind, the most important spaces are the lounging areas where his kids and their friends can pile together to talk, play games or watch a movie. “This house is like a base camp, a huge tent, and these are the places we come together. Our doors are always open. I never know who I will find hanging out here when I come home,” he laughs. His twin 21-year-old sons, Aratt and Ragner, are both studying design; the first reaction of their friends when they come to visit, says Aratt, is often “Wow!” “But no one is jealous,” adds Ragner, “because they know they can move in if they want.”Quinze continues on into a massive, connected loft-like space with a central staircase that leads up to two more storeys. This section of the ground floor was once his studio; it is still filled with models of his public art sculptures, some hanging from the ceiling (his abstract wood-plank installations and aluminium sculptures of wildflowers have been installed everywhere from Paris to London to Riyadh). There are framed painting studies and a wall covered with dozens of photographs. On the second floor is a formal dining room, a riot of colour and pattern. The floor is covered with splattered paint and abstract florals, as is the long oval table. A massive crystal chandelier hangs from a ceiling clad in distorted mirrored tiles. He points to the organised piles of books in the corners. “I have so many books in the house that I have started to make tables from them.” Soon, he adds, he’ll knock down one of the walls to create an extension housing a new wellness room.The house is the one artwork the artist has spent the most time and energy tweaking and evolving. This is partly due, he says, to his complicated childhood. At the age of 14 he ran away from home and, for some time, lived on the streets of Brussels. He blamed a fractious household for his runaway phase, but it was during that period on the streets spraying graffiti that he became an artist (he is entirely self-trained).Living without shelter during that period, he says, made him more sensitive to beauty. “There’s actually an obvious logic to evolve from a street artist to someone making public art,” he says. It also made creating a real home, especially when he started to have children, that much more central to his wellbeing.It’s working in his gardens, however, that really inspires and shapes his art. At his now year-old studio, a massive all-white warehouse in a semi-residential area about five minutes’ drive from his house, he has created a second flower garden surrounding three sides of the building. Often, he starts his work day on his hands and knees weeding and observing the forms the flowers are taking from the viewpoint of a bee or butterfly. He’ll then position himself in front of one of the several oil paintings he’s hung on the walls, put on some atmospheric music – whether the hip-hop group Die Antwoord or Philip Glass – and work, sometimes for six hours straight. The final results are canvases covered in wildly colourful organic shapes, Jackson Pollock meets Monet.Quinze feels an affinity with Monet, both the impressionist master’s work and his gardens at Giverny. In his own garden, Quinze grows a pink poppy. “It’s the same plant that once grew in Monet’s garden,” he says. “We share a passion for studying the impermanence in the beauty of nature.” (Quinze’s most recent work, currently exhibiting at the San Francesco della Vigna church in Venice, is a massive installation of glass objects, ceramic works, and AI-generated video titled Six Testimonials. It’s one of his most immersive yet; he worked with the musician Swizz Beatz to add the medium of sound. “Think of birdsong,” he says. “Sound is one of the senses that helps nature evolve.”) Quinze is seated again on the deck of his garden. “Voltaire was right,” he says. He’s referring to the French philosopher’s famous advice in Candide: cultivate one’s own garden, and exchange the fruits of one’s labours with neighbours and family. “When I dive into the microcosmos in my backyard, it gives me the ability to see things larger, more holistically. When I built that installation in Venice, that came from me being on my knees in my garden.” The next solo exhibition of Arne Quinze’s paintings, Hidden Beauty, opens on 22 September in the Ludwig Museum in Koblenz, Germany

رائح الآن

rewrite this title in Arabic The untamed nature of Arne Quinze

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 خليجي 247. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.