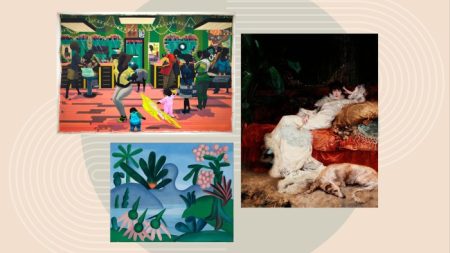

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Tucked behind the Greek and Roman wing of America’s biggest museum, a man is running around, cursing how few power outlets there are in the gallery. He’s surrounded by approximately 641 pieces of art, precariously perched on tables or leaning against walls. Right now he’s holding a giant papier-mâché head made of museum brochures, trying to create order out of chaos.“I’m going to keep a bunch of these water scenes together,” he says, standing in front of a smattering of paintings of lakes, seas and one of a filled sink. He keeps walking. “I thought portraits should go here,” he points. “And the nudes here.” He wanders away, muttering, “Just way more digital art than I expected! I don’t know what I’m going to do about the outlets!”We pass a diorama that presents a Lego rendering of “Starry Night” behind a fabric sandwich. “A lot of mediums,” I say. He’s already halfway down the gallery. “The variety’s what’s so cool about it!” he yells over his shoulder. “It’s just endless!” Then he stops in front of a small statue. “I’m not sure what this is, I think a used salad dressing bottle?” He takes a sniff and continues on. “Pungent smell.”The man is Daniel Kershaw, senior exhibition designer at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This show is unlike any other under his purview. It’s the employee show, Art Work: Artists Working at the Met, which has been running approximately every other year since at least 1935. This year, for the second time in its history, it’s open to the public.The Met employee art show may be one of the best-kept secrets in New York, a city that’s running out of secrets. Any staff member can submit one piece of art and, as far as Kershaw remembers, nothing has been refused. The show is designed, hung, presented and guarded by that same staff — some of the world’s best — who also design, hang, present and guard the 1.5 million works in its full collection, including “The Death of Socrates”, Monet’s water lilies, tools that may be 700,000 years old and a reliquary said to contain Mary Magdalene’s tooth.I’m here to witness the pre-show flurry, as employees submit their works for Kershaw to arrange. I watch as hundreds of museum guards, conservators, art handlers, technicians, curators, masons, interns and cleaners find safe corners to drop objects big and small. There’s a long stuffed Furby in a straw hat, painting itself on a tiny canvas (an ode to Van Gogh’s 1887 self-portrait, which sits upstairs). There’s a giant wooden wrench, by a technician who usually submits giant soup spoons. There’s a painting of clams that’s still wet.A large percentage of the Met’s staff make creative work. Senior security manager Lambert Fernando estimates that 75 per cent of the guards are artists of one sort or another. “And they’re with the art all day!” he says. “They protect it. They’re really its guardians. When you’re with the art like that, it seeps into your brain, and comes out as some pretty wild stuff.”Fernando gestures to his own submission, a small, naked, baby-bodied figurine of Donald Trump, augmented by clay, which sits inside a bell jar to be safely observed. He wanted to make something “uncannily or uncomfortably realistic”. I assure him it’s both.As I wander with Kershaw, a security guard sets down a tiny bust in a box, an intricately carved sculpture of a man that looks like him. “Can you be careful with this?” he asks. “Oh yes!” Kershaw says. “What is it made of?”“Soap,” he says.The guard’s name is Dave Gluzman. I ask about his art. He speaks English slowly. “I just removed anything extra, and it became this,” he says. “His name is Isaiah.”I ask what the piece means to him, and he smiles shyly. “Just soap.”Another guard, Nanette Villanueva, unrolls her canvas to reveal a stunning collage. It’s an indoor scene of everyday items: hangers, sneakers, clutter, a coffee machine. She explains that the piece is made to feel like a puzzle that doesn’t quite fit, “bits of memory caught in a daydream”.Villanueva has been at the Met for 28 years. Like much of the staff, she exhibits her work around the world. She and some colleagues have their work on show now in a small gallery in SoHo, called 201@105. A handful of Met employees have been in the Whitney Biennial.I watch as hundreds of museum guards, conservators, art handlers, technicians, curators, masons, interns and cleaners find corners to drop objects big and small It’s a difficult fact to confirm, but many of the museum’s experts agree that this may be the biggest representation of living artists in a major museum in the US. (This year’s Whitney Biennial, in comparison, had 71.) “You get a slice of what New York artists are up to now that you don’t see anywhere else,” says Kershaw says, who’s been designing the exhibit for about 35 years. And because it contains all this life, he has relentlessly, in his words, “annoyed one director after another” to let him open it to the public. They wouldn’t; one worried that visitors might confuse the art for part of the museum’s collection. But finally, in 2022, the Met’s newest director, Max Hollein, agreed. This year, participation exploded, with more submissions than ever before.The room hums. Dave McCallister works in the security command centre. His childhood BMX bike stands in the middle of the floor, a Diamondback he’s replaced so many parts of that only the ghost of the original bike remains. It’s on display because “I have kids and a job and can’t crash any more”.Michael Greenberger, a copyist who helped co-ordinate the museum’s copyist programme for years, has submitted an almost exact replica of “The Declaration of Love” by Jean François de Troy, except the central female figure is painted over in electric blue. I tell him I love seeing the object of desire removed from an 18th-century painting. It changes the entire painting. “Yes!” He says. “The simplification helps people understand art. It somehow makes it more interesting.”The staff show is one of 13 projects Kershaw is designing at the museum, and one night he brings me to another: the unveiling of a vast three-part Tiffany Stained-Glass Window he helped to install in the American Wing’s permanent collection. This acquisition was made possible by a long paragraph of donors, and he sweeps me through the medieval wing to attend a champagne toast. On the way, he calls to a man rolling a garbage cart down the hall.“Are you submitting a piece this year?”“Yes!” the man calls back.Kershaw tells me this man submitted a fascinating found-art lamp once, which was an homage to Duchamp. “You just don’t know who someone is based on their art!” he cries with joy, and we enter the American Wing and each take a champagne coupe.I watch Hollein congratulate everyone involved in the window, a 1912 opalescent glass masterpiece more than 10 feet wide, designed by Agnes Northrop in the studios of Louis Comfort Tiffany, and built largely by women. The piece was finicky, Kershaw says, and outrageously delicate. I stand among the donors, who are, quite literally, in pearls and heels. We raise our glasses, then Kershaw and I scurry back to the employee drop-off, and I realise that Met life really is entwined, a liquid flow between larger than life and regular life.An 80-year-old woman wearing a floppy sun hat walks past me with a cane and cart. Her name is Syma. She teaches art classes to school groups, and claps in delight when I ask to interview her. This bust, she explains, pointing at a perfectly round head — half carved into a face, half smooth — is of the goddess Astarte, who represented both fertility and war. It’s a cast of a clay original she made in 1982. “Things were challenging then,” she says. “My house and studio had burnt down. I was a single mom. I wanted to take care of my daughter, and keep making art.” She put two slips of paper into the mouth of her sculpture: a wish, that she’d be able to keep on, and a promise that she’d do her part too. Then she closed up the mouth.I ask what the sculpture makes her think of now. “I think of my promise,” she says. “And I think, wow, she gets to be in the Met-ro-politan Museum! I’m doing my part, keeping on. They’re doing their part. What else can I ask for?”I stand for a minute, watching the commotion. “It’s all really something,” I say. The woman next to me nods. Her name is Nancy Rutledge. She is a manager in the imaging department. I ask what she’s included and she walks me to a black-and-white photograph of a mountain. There’s a tiny figure in the corner, fishing peacefully.She and her boyfriend both loved photography, she tells me. But during the pandemic, he died. He was the first EMT (emergency medical technician) in New York City to die. For two years she couldn’t touch a camera. But then she started doing something she calls sunset therapy: “I took a picture of a sunset every day. Just to remind myself, there will be another beautiful day.” She took this photo in 2022. The figure, she says, seems to be enjoying life, and that reminds her of him.When people enter the gallery to submit their work, they approach an intake table of volunteers led by Alethea Brown. Brown runs the Met’s box office. She’s been keeping the show organised since the 1990s and tells me, laughing, that it just takes patience. It’s not the volume that bothers her. You just need to know the idiosyncrasies of your colleagues when nearly 700 living artists are hand-delivering their art to you with special instructions.Is there anything like it? I ask. She doesn’t think so. It’s not like curating a Van Gogh exhibit, where there’s one artist, and he’s dead. “And even when shows have a lot of works, we co-ordinate with galleries and use our own collection.” Then she rolls her eyes, smiling. “Also, those shows take two to five years. They don’t do it in a month!”Before I leave, Kershaw and I notice a new piece has been delivered. It sits alone in the middle of the gallery, left by an art handler. The work is still in its crate, but includes a handwritten note: “Please notify facilities of ‘garbage’ elements so as not to throw out,” it reads. “Previous exhibition elements were thought to be actual garbage and discarded.” Beneath it is a diagram — side view and aerial — to clarify where the “garbage” should sit.Kershaw and I exchange a glance. You don’t know who someone is based on their art, I think, remembering the Duchamp lamp. But you also don’t know who among us is an artist. Better to assume we all are. ‘Art Work’ is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, November 18-December 1. Lilah Raptopoulos is a US culture writer and host of the FT’s Life and Art podcast; [email protected]

رائح الآن

rewrite this title in Arabic The Met’s secret employee art show is no longer secret

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2024 خليجي 247. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.