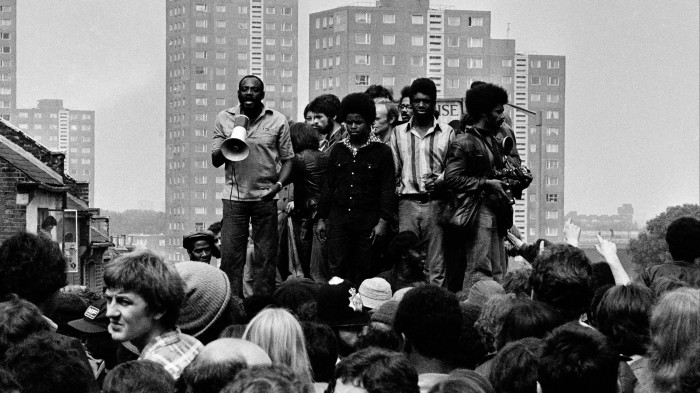

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Eyes creased in glee, mouth breaking into a wide grin, body tilting forward in laughing conspiratorial pose, the 13-year-old Black kid on the poster outside Tate at Millbank entices you into the exhibition The 80s: Photographing Britain, promising high spirits and humour.Fat chance. Inside, grey tones and preachy attitudes posit the clash of race and class during a decade of Conservative rule — commemorated in Anna Fox’s paintball-splattered “Margaret Thatcher Target” — as the grim ancestor to today’s identity politics. This is perverse, because the best photographers featured are searching and original. Joy, interest and humanity are here, but to find them you have to play hide-and-seek through a mush of mannered miserabilism.It didn’t have to be like this. Ting A Ling, the teenage poster boy, is a star of the terrific “Handsworth Self Portraits Project”, for which passers-by of all ages and ethnicities were invited through the summer of 1979 to step into a pop-up photo studio and curate their own image. It’s Birmingham’s cheerful selfie version of August Sander’s Weimar portraits Face of Our Time. Derek Bishton, one of the organisers, remembers: “We were knocked out by the diversity of the people and the way they had pictured themselves — so natural and dignified.”Aiming to show how the camera “became a tool for social representation” in the “long 1980s”, giving marginalised groups confidence and authority through powerful self-depictions, Tate has real scope for an optimistic story.There is Pogus Caesar, a pointillist painter who, encountering a Diane Arbus book, turned to photographing his own milieu: classical close-ups of anonymous Black faces emerge majestically from dark grounds in the series Into the Light. In Vanley Burke’s wonderfully detailed “Outriders Head the African Liberation Day Rally, Rookery Road, Handsworth”, Black cyclists ride into town with the glamour of Roman charioteers; Burke is master of bold contrasts, dramatic mises en scène. Zak Ové, today an inventive multimedia sculptor, was once a charismatic young photographer: his dreadlocked Black violinist in white shades haloed by spotlights, “Underground Classic (John Taylor)”, fizzes with life. Best of all, these charged, independent Black portraits don’t surprise: that battle of representation has been won.Each of these pioneering artists deserved a room of his own. Instead, Tate scatters their works, denying distinctiveness, in gallery upon gallery swollen with records of anti-racist rallies, miners’ strikes, poll tax protests, Greenham Common sit-ins. A few are memorable: Syd Shelton’s anti-National Front demonstrators silhouetted against Lewisham’s tower blocks; John Harris’s truncheon-wielding officer at the Battle of Orgreave threatening a cowering fellow photographer. Many are unremarkable documentary shots taken for leftwing media outlets such as “Labour-Now”. The opening work, David Mansell’s depiction of Jayaben Desai, an Asian woman leading the “strikers in saris” staring down police in north-west London, sets the hostile, self-righteous tone.The “Landscape” gallery focuses on Ingrid Pollard’s loud text-and-image series The Cost of the English Landscape: “Keep Out” and “No Trespass” notices punctuate rural “managed landscapes” of dry stone walls, gates, telegraph poles. The message? Pollard says it is that “stereotypes about Black people are constructed in exactly the same way.”The section “Remodelling Histories”, a puerile disappointment, shows Jo Spence’s shrilly downbeat self-portraits — wearing novelty glasses and shrieking while reading Freud’s On Sexuality; half nude, surrounded by domestic accoutrements of broom and milk bottles.Growing discrepancies of wealth, and those between left-behind regions and the booming capital, shape any narrative of the decadeSpence has 27 works on display. The incomparable Don McCullin has three. Instantly in his trio depicting Jean, homeless in Whitechapel, grimy hands with long elegant fingers softly clasped, worn furrowed face still expressing curiosity, you find individuality, a sort of beauty amid suffering, psychological and formal strength.Homelessness suddenly visible in London is one of my visceral 1980s memories, alongside excess — Big Bang euphoria in the City, big hair and shoulder pads in its bars. Growing discrepancies of wealth, and those between left-behind regions and the booming capital, shape any narrative of the decade. It was showcased at the time, for example in Another Country in 1985 at the Serpentine, Kensington Gardens, exhibiting two outstanding chroniclers of northern deindustrialisation.One of these, Graham Smith, is entirely absent here; from the other, Chris Killip, are a handful of his Seacoal images charting declining Northumberland. “Brian in a Duffle Coat”, facing an empty sea beneath scudding clouds, is emblematic of a vanishing milieu, of ageing and loneliness. Killip’s empathetic pictures, and John Davies’s sweeping, geometrically centred post-industrial landscapes in flux — “Agecroft Power Station, Pendlebury Salford, Greater Manchester”, “Durham Ox Pub, Sheffield” — are the show’s compositional and emotionally gripping highlights, evoking moments in history but also the mystery of time and change.Smith stopped exhibiting in 1991, and Killip left Britain the same year. By the late 1980s, monochrome documentary styles were on the way out, punchy saturated hues and the glare of daytime flash were in. The Sunday Times, launching its lifestyle magazine, sacked McCullin in 1983.Working exclusively in colour since 1982, depicting working and middle-class leisure, Martin Parr — so gifted, so ubiquitous, so coldly detached — shifted the terrain. His Merseyside waitress in an ice-cream parlour in “New Brighton, England” is as defiantly blank as Manet’s barmaid at “Les Folies Bergère”. Parr’s guzzling girls (“Strawberry Tea, Malvern Girls School”) and Tory toffs (“Conservative Election victory party”) illuminate, Tate says, “the excesses of Thatcherism . . . caricatured vividly, garishly and critically in the bright colours of consumerism”.Actually, these sour, satirical/complicit images unnerve by ambiguity, and Parr is messenger of more global disaffections. “The Martin Parr-ization of the world . . . exploding in colour, tourism and kitsch”, as Swiss photographer René Burri called it, was a prophecy of now.Parr adeptly chronicles increasing cultural divisiveness, a phenomenon to which Tate should bear witness rather than contribute. For most dispiriting here is the exhibition finale “Black Bodyscapes” and “Celebrating Subculture”, extensive presentations of photographers challenging “conventional representations of Blackness and queerness”. They feel belligerent rather than advocating tolerance.An American 1990s Black artist holds this stage: Lyle Ashton Harris, who explains his “Constructs”, life-size self-portrait nudes in ballet poses, as “relationally exploring my positionality” and an “aggressive assertion of sex-positiveness”. Ajamu X’s roll call of Black male nudes — “Bodybuilder in Bra”, “Self-portrait in Wedding Dress”) and Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s fetish portraits (“The Golden Phallus”, “Every Moment Counts (Ecstatic Antibodies)”) — are among many similarly self-important, antagonising works.Was Harris — the show’s only non-Brit — chosen precisely for this stance? It both alienates, and misrepresents history: new, truly inclusive approaches to depicting LGBT+ communities were important in photography’s liberalising trajectory of this period — for example Lisetta Carmi’s marvellously sensitive record of Genoa’s 1960s trans community, making us all question how we decide who we want to be.Tate’s show is worse than a squandered opportunity. Who is it for? It reflects a vanishingly small proportion of 1980s experience. It plays up divisions, and fails even to mention unifying events such as the 1985 Live Aid concert and the 1981 royal wedding. Thatcher boasted “there is no such thing as society”. A museum’s role is not to pander to race and gender divisions but to prove her wrong, and show art to which everyone can respond. November 21-May 5, tate.org.ukFind out about our latest stories first — follow FTWeekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen

rewrite this title in Arabic The 80s: Photographing Britain review — Tate’s stark portrait of Thatcher’s decade

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2024 خليجي 247. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.