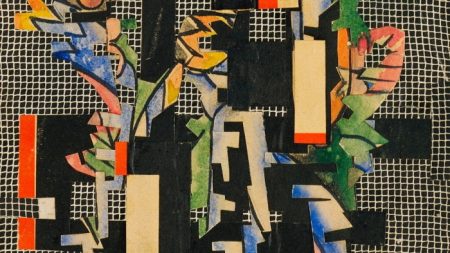

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Stay informed with free updatesSimply sign up to the House & Home myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.There is a scene in the third episode of Sunny, one of this summer’s most talked about sci-fi thriller television series, in which lead character Suzie — played by a fabulously styled Rashida Jones — offers a brief summary of her recent woes and revelations from the comfort of her acid-yellow Togo sofa: “Apparently my lifestyle has been afforded by robot sex and murder,” she says, sipping a cocktail from a bent stem martini glass. “Well at least it’s a really nice lifestyle,” offers her friend Mixxy, moving from the couch to a cartoon-like, tubular, red 2009 Moustache Bold design and then caressing its frame: “I’d robot murder someone for this chair alone.”Each episode of Sunny comes with a Saul Bass-inspired title sequence that serves as shorthand: this is Japan, at some point in the future, but a place that also looks like a past that never really existed. Suzie’s husband and son have apparently been killed in a plane crash, and she has recently taken delivery of Sunny, a “homebot” from her deceased husband’s company. Layers of intrigue and mystery unfold episodically, but it’s the style as much as the story that pulls you in. Cocktail bars glow ruby red, grocery stores are cold dark blue.As an obsessive of Japanese design, I am thrilled by how perfectly Sunny captures the anachronisms of a culture associated so strongly with innovation, without veering into cliché. I’ve spent amazing days at both the Issey Miyake and Yohji Yamamoto design studios, observing the machinations of some of their specialist departments, only to get a taxi back to my hotel driven by an elderly man reliant on a paper guidebook with a set of maps and a magnifying glass, in a car festooned with antimacassars. Sunny is set in Kyoto, not Tokyo, which is significant. It could easily have slotted into Shinjuku’s neon mazes or the high-rise towers of the modern capital. Rashida Jones’s character could have grieved and unravelled surrounded by Tadao Ando modernism, in an apartment like Cate Blanchett’s in Tár — but instead each frame is full of domestic warmth, shadow and primary colour. It positively rails against the AI that is an integral part of its plot.Suzie’s house is lavish, but low key. The wooden grids, patterned floor, shoji screens and internal garden space mark it out as fundamentally traditional — all the codes of the architecture remain grounded in the rise of the samurai class of the 12th century, when houses became places for ceremonial social occasions, and needed rooms demarcated accordingly.Any technology is blended delicately and scaled back from what we have in reality right now. Phones are simple devices to communicate by voice, not text, and when Suzie scrolls through online content in bed the screen has the visual quality of a paper screen. The translation earbuds that Suzie uses to communicate daily are surely just around the corner for our own reality, and are discreet — in Japan, where high tech can be considered vulgar, it is frequently either made kawaii (childish and super cute) or hidden entirely. If you stay in a luxury ryokan, you might find the TV disguised by a shroud of beautiful embroidery. This is Japan, at some point in the future, but a place that also looks like a past that never really existedThe use of primary colour blocking in Sunny’s set design is powerful, extending to the noir-inflected lighting. An opening scene has red drenched backlighting, as a robot commits homicide. Blood splatters against a panel of upholstery. The lighting balance adjusts to reveal that the blood is most definitely red, but the fabric is a sunshine yellow. The Japanese consider yellow a sacred representation of nature and life, but the nuance of colour in Japan can be unfathomable to the outsider. There is an exhaustive list of dentōshoku, which attributes meaning to individual shades of a colour. White is a de facto wedding choice in the west, but historically funeral garb in Japan. The yellow that appears on certain table tops and in the bloodstained fabric in Sunny is a juvenile, nursery kind of yellow. It’s been chosen to be jarring. It’s also referenced in a flashback, as Suzie says goodbye to her apparently doomed husband at the airport, and mutters “yellow” as she looks at his shoes. There is something so chic about the blood on that fabric, so . . . Kvadrat. Elsewhere there is an incredible green carpet in the broad expanse of the 1960s Kyoto International Conference Center, playing the part of ImaTech HQ, where the homebots originate. The building itself is remarkable — a Brutalist take on traditional temples, with sloping walls. That green is even more impressive: an overtly retro 1950s shade. So totally Japanese.Looking at Suzie’s house in Sunny, it’s impossible not to exoticise something so far from our clumsy western blueprints. Those shoji screens and the grid patterns — with ecclesiastical stained-glass panels — and the proliferation of rich wood, look like an impossible luxury. But the reality, as Jun’ichirō Tanizaki documented in his cult 1933 essay, In Praise of Shadows, is that it’s achievable. We just haven’t bothered. We’re obsessed with over decoration and bright lights, whereas the architectural aspects in Sunny are pretty much the whole decor. “The beauty of a Japanese room depends on a variation of shadows,” Tanizaki writes. “Westerners are amazed at the simplicity of Japanese rooms, perceiving in them no more than ashen walls bereft of ornament . . . Of course, the Japanese room does have its picture alcove, and in it a hanging scroll and a flower arrangement. But the scroll and flowers serve not as ornament, but rather to give depth to the shadows.” Get better — and less — lighting. Embrace the smell of tatami mats and hinoki wood. You can, of course, also get a yellow sofa. Find out about our latest stories first — follow @FTProperty on X or @ft_houseandhome on Instagram

rewrite this title in Arabic Robot sex, murder and inspiring interiors: the dystopian allure of TV’s Sunny

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 خليجي 247. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.