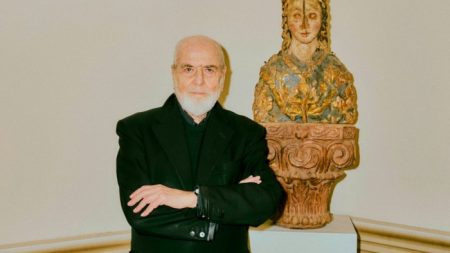

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic “Fundamentally, The New Real is a Western,” says David Edgar of his latest play for the Royal Shakespeare Company. Just a minute. A Western? The New Real, produced in association with Headlong theatre, is an epic, cut-and-thrust political thriller about election strategists, pinging back and forth between the US and eastern Europe during the early 21st century. Dirty tricks, yes; bar brawls, yes — but horses, Stetsons and saloon doors? Not so much.“Well,” says Edgar, with a smile, “it’s about two people being called into the village and ending up in a High Noon shootout against each other.”In fact, it is one of two new Edgar plays featuring a high-stakes showdown between allies: a metaphorical “shootout” that keys into a much broader issue. In The New Real — subtitled “an origin story” — two American political strategists grapple with the complex legacy of the collapse of the communist bloc and a world rapidly realigning around new political coalitions. The second new play, Here in America, peers into the 1952 falling-out between playwright Arthur Miller and director Elia Kazan, when the latter named names to Senator Joe McCarthy’s anti-communist House Un-American Activities Committee.Coursing through both works are battles between principle and expediency, the interplay between power and control of the narrative, and the struggle to maintain democracy in the face of authoritarian populism. Edgar first drafted them before the pandemic. He points out that the intervening couple of years have only increased their topicality. “I do feel we are in the most paranoid, polarised period of American politics there has been since the early Fifties,” he says. “I think Trump has, both in style and substance, a great deal of what we think of as McCarthyism. So I think that beast is back.”Now 76, Edgar is one of Britain’s leading political playwrights: a tireless chronicler of the shifting sands of power and ideology. He started writing plays as a child in Birmingham, performing them in a garden shed converted into a tiny theatre by his father, and first had a drama professionally staged in 1970 (Two Kinds of Angel), followed by more than 60 works over the next five decades. A long association with the RSC started with his 1976 work, Destiny, about the National Front, and included a hit adaptation of Charles Dickens’s Nicholas Nickleby. He founded the pioneering MA in playwriting studies at Birmingham university and has written an invaluable book, How Plays Work.Yet he has lost none of his appetite for the fray. Courteous, erudite and wry, he arrives for our interview buzzing with recommendations for books and documentaries that shed light on our current political turbulence.Edgar has written a trilogy of plays (The Shape of the Table, Pentecost and The Prisoner’s Dilemma) set in eastern Europe after the collapse of the Soviet Union, drawn from his own visits to the area during the 1980s and 1990s. He noticed even then that the views being voiced did not align strictly with what the western world saw as left- and right-wing politics.“You would have conversations with people who liked the arts, believed in free speech and civil liberties, were liberal on sexual and gender issues. But sooner or later, over the fifth Slivovitz, they’d say, ‘The only thing we can’t understand is why you’re so hostile to that wonderful woman, Margaret Thatcher.’ They believed in economic and social liberalism at the same time. And of course, our politics has traditionally not worked like that.” Those changing priorities have spread, he adds, picking up on voter discontent, catching traditional western parties on the hop and producing a wave of destabilising events. The New Real traces that process across the first 20 years of the 21st century. It’s the subject too of a new book, The Little Black Book of the Populist Right, co-authored by Edgar with Jon Bloomfield.So what price political theatre? Can it make any difference in such a fractured world? In 2018 Edgar wrote and acted in Trying It On, in which he was robustly challenged by his younger, firebrand self (via a tape recorder) about what he had achieved. Nonetheless, he thinks that political drama is currently in rude health.“Since the beginning of the last decade, since the 2008 crash, the Arab Spring, Occupy, the #MeToo movement and Black Lives Matter, politics has returned to the centre of life,” he says. “Theatre has returned to what it was in the Seventies: a place where you go to see ideas expressed in a politically charged way.”Political theatre has always morphed to suit the times, he suggests. He identifies a switch in the late 1970s from big history plays to “snapshot plays” focusing on a particular issue as symptomatic of a greater societal shift. Examples might be David Hare’s Pravda (about Rupert Murdoch’s influence), Caryl Churchill’s Serious Money (about the City) and Jez Butterworth’s Jerusalem (about Englishness): “Plays that have a size beyond their subject,” he calls them.Frequently a champion of other writers, Edgar admires current political dramatists such as Peter Morgan and James Graham, and the way contemporary theatre incorporates politics into its practice, aiming for diversity in casting and the sustainable use of resources. While a play might not change the world, it can, he argues, articulate problems or illustrate how systems work.“I think the most influential piece of political theatre of the 20th century was Joan Littlewood’s Oh, What a Lovely War!, which handed on a particular, and in my view accurate, view of the first world war,” he says. “The Tricycle Theatre’s ‘tribunal plays’ [verbatim accounts of public inquiries in Britain] added up to a portrait of how the British establishment tried to cover things up.”Occasionally, political drama can make a real difference. “We’re talking in a year that saw probably the most directly impactful piece of television drama ever: Mr Bates vs The Post Office,” says Edgar, referring to the ITV drama about the Post Office scandal, in which hundreds of sub-postmasters were wrongly prosecuted for theft or fraud.The series not only produced a widespread public outcry, it prompted the government to introduce legislation. It was evidence that politically engaged drama can sometimes galvanise change. That, together with the quantity of new plays hitting our stages, is cause for celebration for Edgar. “I think it’s a very rich time for political theatre.”‘Here in America’, September 14-October 19, orangetreetheatre.co.uk; ‘The New Real’, October 3-November 2, rsc.org.ukFind out about our latest stories first — follow FTWeekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen

rewrite this title in Arabic Playwright David Edgar: ‘It’s a very rich time for political theatre’

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 خليجي 247. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.