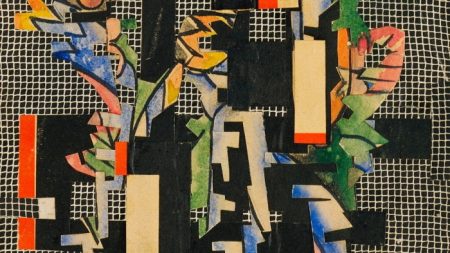

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Unlock the Editor’s Digest for freeRoula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.In Mohammed Sami’s enigmatic painting “The Grinder” (2023), four empty turquoise chairs at a round table are viewed from above, amid an expanse of mud-coloured carpet. The mixed-media work on linen is dominated by a shadow cast by what might be a ceiling fan or helicopter blades — reminiscent of the film Apocalypse Now, in which remembered Vietnam helicopter gunships morph into the rotating fan above Captain Willard’s bed.As you study Sami’s unsettling painting, the overhead perspective inexorably turns the shadow into digital crosshairs hovering over an unwitting target. As is usual in his work, no figures are depicted, but powerful people are a palpable presence. Rather than the usual suspects placed under surveillance, this painting appears to turn the tables, putting in our sights the decision makers and controllers normally invisible behind closed doors — watchers, watched.“The Grinder” is the key opening work of After the Storm, a solo show at Blenheim Palace by the Baghdad-born artist, who left Iraq in the years after the US-led invasion of 2003 and found refuge in Sweden in 2007. (He now lives in London.) Marking 10 years of the Blenheim Art Foundation’s contemporary art programme — previous artists have included Ai Weiwei, Jenny Holzer and Tino Sehgal — 14 of Sami’s new paintings on linen are on view to the public in parts of the Duke of Marlborough’s stately home in Woodstock, Oxfordshire. Most were painted this year in response to the palace and its collection. John Vanbrugh’s Baroque masterwork, now a Unesco World Heritage Site, was completed in 1722 as the gift of Queen Anne to John Churchill, first Duke of Marlborough, for winning the 1704 Battle of Blenheim (Blindheim) in Bavaria — a rout that “changed the political axis of the world”, wrote his descendant Winston Churchill, who was born there. The palace was created to glorify martial victory over the French in the war of the Spanish Succession.As you walk through the courtyard, past cannon and Roman centurions, a carved clock tower designed by Grinling Gibbons shows the lion of England savaging the cockerel of France. On the apex of the pediment, a helmeted Minerva, goddess of war and art, lords it with her trident over cowering French POWs, hands bound behind their backs. “The Grinder” hangs in the Great Hall, whose painted ceiling by James Thornhill shows the duke in Roman attire presenting his battle plan to a helmeted Britannia, seated proprietorially on a globe, as minions pile up the spoils of war.Art and architecture have played a key role in sustaining and memorialising conflict. Yet the strategic insertion of Sami’s works here profoundly alters the visiting experience. Placed facing a vitrine of Napoleonic toy soldiers, “The Grinder” plays off these war games with the remote targeting of modern warfare. It also puts an irresistible gloss on the huge blue and brown eyes which the ninth duke’s wife had painted looking down from the portico ceiling — transforming them from a kitsch romantic gesture into an Orwellian Big Brother.Blenheim’s prized tapestries celebrate sieges and battles: even their borders seethe with muskets, helmets, bugles and drums. Sami’s unsettling paintings sharpen our awareness of this insidious visual propaganda, but also the suffering it omits. In “Chandelier”, exhibited in the Red Drawing Room, what appears to be the painted shadow of a six-candle Baroque light suspended from the ceiling resembles a spidery drone — a sinister reminder of how everyday objects can trigger traumatic memories for people who’ve survived conflict. Stencilled on a painted background resembling chipboard is the start date of the US-led invasion of Iraq: 03/2003.Hanging amid the tapestries is Sami’s “Reborn” (2023) — one of a scabrous series depicting medal-adorned military men. While the bright green of his uniform picks up the chair covering, only a dimpled chin is visible of the face. The rest is obscured by a thick layer of paint, sand and dust, on which a moth appears to have settled.Two more obscured portraits found in the library next to a marble statue of Queen Anne make explicit links between past and present wars. “Wall of Cockroaches” veils an officer’s head in a curtain of dripping yellow paint, another trompe-l’oeil insect settled where his face should be. It recalls the grotesquely corrupt generals depicted in the expressionist paintings of Serwan Baran, a conscript in the first Gulf war who represented Iraq at the 2019 Venice Biennale. In Sami’s “Stiff Head,” the face obliterated by caked and cracking beige paint is that of a cavalry officer, his faded red uniform adorned with gold brocade.This dialogue with the palace continues in a roomful of Meissen and Sèvres porcelain. In “Wiped Off”, a mop stands erect as a rifle in a pool of blood against a red damask wall, shattered crockery strewn around. The room label, reminding us that English fine bone china was invented in 1749 when porcelain was supplemented with bone ash, hints at a link between broken plates and blasted bodies. In a more benign world, the tied cloth bundles in “The Statues” could be garden umbrellas waiting to be unfurled. Here, next to ceremonial flags in the state room where the painting hangs, the objects resemble body bags.Blenheim’s connections to 20th-century warfare become explicit in Sami’s “Immortality”, which is hung in a corridor of family portraits. Based on a 1941 photograph of Churchill, the shadowy image of a hunched figure with splashes of white at collar and cuff is unmistakable.The most impressive of Sami’s works on show here are in widescreen. The 5.5-metre “The Eastern Gate” (2023), which hangs in front of a silver centrepiece sculpture by Robert Garrard of the Duke of Marlborough on horseback, offers a breathtaking vista of Baghdad in an ethereal orange haze, with tank tracks advancing across the foreground. By contrast, the field of sunflowers in the dripping impasto of “Massacre” (2023) has been devastated not by tanks but by cavalry hooves.The final painting in the chapel, evoking a couple underwater or vaporised by a blinding light, is “Hiroshima Mon Amour”. A label asserts that this work is “a departure from Sami’s personal field of experience”. Yet the artist’s insistent questioning of Blenheim’s art and history makes the universality of his work crystal clear.To October 6, blenheimpalace.com

rewrite this title in Arabic Mohammed Sami, Blenheim Palace exhibition review — the grief underneath the glamour of war

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 خليجي 247. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.