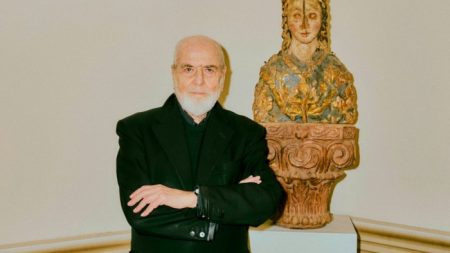

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Unlock the Editor’s Digest for freeRoula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.James Earl Jones once reflected that “one of the hardest things in life is having words in your heart that you can’t utter”. Unable to find his voice as a child because of a severe stutter, he was brought out of his shell by poetry. His high school English teacher found that Jones was able to speak in front of the class when reciting his own verse. Before long, he was involved in debating and drama. His early years of introspection and isolation were over. Jones, who has died at the age of 93, was in many ways defined by voices and silences. It was the title he gave to a 1993 memoir co-written with Penelope Niven. For decades his soulful, basso profundo tones travelled far, notching up more than 100 screen credits and taking scripts — a “sanctuary” for stutterers — in new directions on Broadway and in Hollywood. With a “sound Moses might have heard when addressed by God”, in one critic’s reckoning, he breathed life into tragic heroes and immortalised new characters, notably Darth Vader in Star Wars and Mufasa in The Lion King. “In a very personal way, once I found out I could communicate verbally again, it became a very important thing for me,” he told The New York Times in 1974. “Like making up for lost time, making up for the years that I didn’t speak.”Born in January 1931 in Arkabutla, Mississippi, Jones was raised by his maternal grandparents after his father left home to act and his “mysterious, aggressive, unpredictable” mother remarried. Life at home was not straightforward. Jones remembered his grandmother, who was of African-American, Cherokee and Choctaw heritage, as “the most racist, bigoted person I have ever known”. After the family’s move to Michigan when Jones was five, he developed the stammer that rendered him unable to speak to people for many years. He did not believe that “overcome” was the right way to describe his later ability to talk, insisting in 2014 that he was “essentially still a stutterer”. But parts in summer theatre shows, where his grandmother was his “best audience”, and later dropping medicine for drama at the University of Michigan, allowed him the joy of speech.After a stint in the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, where he reached first lieutenant, Jones made for New York in 1955. By then, his father was a moderately successful actor and the pair lived together and appeared on stage, though the gap of time meant a friendship was the most they could strike up. Jones’s early work included Joseph Papp’s New York Shakespeare Festival. Being spotted by Stanley Kubrick in The Merchant of Venice led to his film debut in Dr Strangelove in 1964. Jones’s break came in 1967 with The Great White Hope, in which he played a character based on the boxer Jack Johnson grappling with the sport’s racism. The play transferred to Broadway the next year and won its leading actor a Tony. A Golden Globe and an Academy Award nomination followed a film version in 1970.Titular Shakespearean roles followed, including King Lear and Othello, although his most memorable came from a galaxy far, far away. At $7,000 for a day’s work, Jones was not well paid for voicing Darth Vader. But, he said, he didn’t mind. It was another role in his “journeyman” career. “If I don’t get you, I’ll get your grandchildren,” he quipped.Jones, who was married twice and is survived by a son, was awarded the National Medal of Arts by then president George HW Bush in 1992. In 2011, he joined the select group of actors to have won the EGOT (Emmy, Grammy, Tony and Oscar). He was also the first African American to have a regular role in a US soap opera and gave a stirring theatrical performance as Troy Maxson, the embittered Black patriarch in August Wilson’s Fences. Yet he maintained that he was not an activist, even if the civil rights movement created “a certain energy . . . for Black actors”. His craft was his concern. “If I can’t change people’s minds, I can change their hearts,” he said. Adrian Lester, who played Brick, his son, to Jones’s Big Daddy in a 2009 all-Black casting of Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, told the Financial Times that Jones “took a different route” to contemporaries such as Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte. But, he said, he was “an example of everything you think you want to be when you get older as an actor: to still be free, to still be open, to still be asking questions”. “James wanted to respect himself inside his work,” Lester added. “He was constantly searching for a better way to do his job, and he never gave up that search.”[email protected]

rewrite this title in Arabic James Earl Jones, actor, 1931-2024

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 خليجي 247. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.