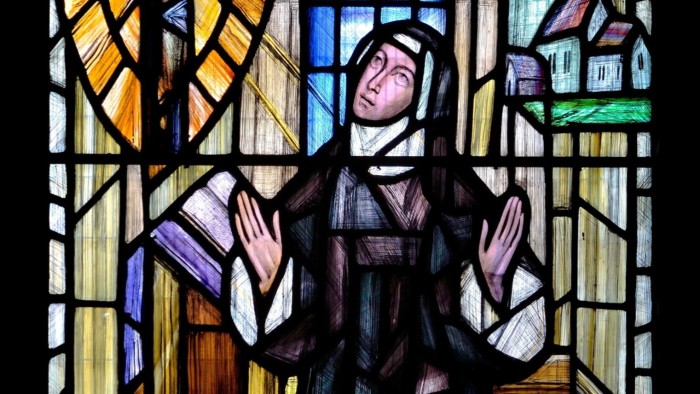

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Books purporting to explore and explain the grand mystery at the heart of things seem to be a dime-a-dozen these days. Two recent efforts by esteemed British writers stand out, their humility a refreshing counterpoint to the cheap dogma or faux-esotericism peddled by some others. Drawing on their authors’ deep and wide-ranging curiosity — neither are scientists, nor religious thinkers per se — they do not presume to answer or resolve anything. Thank goodness.The Point of Distraction, by the 2019 Wellcome Prize winner and journalist Will Eaves, is a brief yet elegant excursion into the nature and execution of creativity. (Anyone expecting a book on the future of the attention economy, say, or on the function and uses of profitable boredom, might feel a bit misled by the title; each chapter is rather punctuated by a new solo piano piece, composed and notated by the author himself. No matter!) While modest to a fault, occasionally Eaves can’t stop himself meting out the odd barb, as in his criticism of successive governments’ failure to equip children with even a basic education in music and the arts. “[The] reluctance to teach it, the fear of owning it as a liberating experience, and the political aversion to making art in general a serious object of study — all these things are . . . highly exclusionary,” he insists. “Music, in all its forms, notated or not, takes everyone seriously.” There’s no doubting his sincerity: Eaves is trying hard to grasp at something ineffable and inexplicable, and that, he believes, should be accessible to all. It is finally “courage”, he says, with all the force of a revelation, that he discovers “at the point of distraction.”Similarly inclusive is Simon Critchley, an academic philosopher who has written riveting studies of Aristotle, Nietzsche and the Greek tragedians — as well as his beloved football (he is a passionate Liverpool fan, more’s the pity), David Bowie, and baldness. His new subject is “mysticism”, hard as that is to pin down. Mysticism certainly seems to be a phenomenon as old as humanity itself, despite being stubbornly resistant to rational definition. Whether so-called “mystical” experiences are felt to be religious, spiritual, aesthetic or something else altogether, people have been trying to report, describe and make sense of this strange kind of ecstasy for a thousand years. Mysticism is “experience”, as the devotional writer Evelyn Underhill put it in 1911, “in its most intense form”.Critchley acknowledges Underhill’s stellar groundwork and takes the baton in “telling the story” himself. In this highly erudite and often joyfully exuberant book, he wonders what it might be to “get outside oneself, to lose oneself, while knowing that the self is not something that can ever be fully lost”. Critchley approaches his subject with humility and from many angles: as a ‘felt’ thing, à la RousseauA self-proclaimed atheist as a younger man, Critchley wrestles with the knotty unknowable-ness of life’s unanswerable questions. He approaches his subject with humility and from many angles: as a “felt” thing, à la Rousseau; more simply, as “a way of being”, the “timeless emptying into time”; and — importantly — as something that could be ours to access freely, if we could only open ourselves to it. (“But one can try,” he encourages, like a benevolent drug-pusher.) His exploration is largely a convincing and absorbing one.While Eaves drops Scarlatti, Stevie Wonder and Succession into the mix, Critchley’s more comprehensive survey starts with Dionysius (c500) and traverses early medieval mystics — most of them elusive European females with names such as Christina the Astonishing (1150-1224) or Mechthild of Magdeburg (c1207-82) — via fictional figures such as Hamlet and obscure 1970s German punk-rock bands. He focuses especially on three modern North Americans: Anne Carson, in particular her 2005 book Decreation; Annie Dillard, particularly her metaphysical theodicy in Holy the Firm (1977); and TS Eliot and his “Four Quartets”. Despite the inclusivity of the title, Critchley’s emphasis is on western mystics. All of them apparently owe a debt, whether they know it or not, to his “heroine”, the anchorite Julian of Norwich (c1342-1416), in particular the “13th Showing” from her work documenting mystical visions, from which her most tender and immortal phrase comes: “It was necessary that there should be sin; but . . . all manner of thing shall be well.”Like Eaves, Critchley is a generous enthusiast, as unpretentious as he is distinguished. Currently Hans Jonas professor of philosophy at the New School for School Research in New York, he has been named as one of the most influential philosophers today. For all his readability, he is a serious academic. You have to pay careful attention. But it pays off: this book is a real intellectual adventure. “Let us go a little deeper . . .” he announces, and he’s off again, powered by a childlike and communicable curiosity. At times he repeats things he has said in other chapters. But the repetition seems to be an act of mulling, an attempt to discover what else might come up. “I still believe in the centrality of the problem of nihilism,” he concedes. “How to find meaning in an apparently meaningless cosmos.” But, for him, “mysticism” is the “fiery core and beating heart” of all existence.Of course, genuine mystics had no idea they were practising mysticism, either in a religious or an aesthetic sense. Despite his cringing self-awareness — he invokes a brief personal experience at Canterbury Cathedral as a teenager — Critchley does seem to be one of them. On Mysticism is essentially a manifesto of surrender, “existential and practical”; freeing ourselves from our “standard habits”, our “usual fancies and imaginings” — and, in so doing, being newly receptive to wonder, whether spiritual transcendence, or sex, or Beethoven’s late quartets, or the “popular music that many of us care about most and understand least”. Presumably the solitary anchorite Julian had no idea that her “showings” would have resonated across the centuries, and in carnal and sonic form too. But that yields another shard of awe: what else might be lying in wait for humans in the future? On Mysticism is a meandering delight, as quietly soul-nourishing as it is brain-stretching. Critchley, like Eaves, never presents a didactic answer to any concrete question — he is too clever for that. But his writing is an antidote to the “visceral, existential doubt” that can tear “away at us like rats gnawing under the floorboards . . . that leaves us feeling derelict and abandoned”.Sceptical we might be, but these authors seem convinced that we all have a “spiritual hunger” that could be released by being open to certain glimmers of ecstasy. “These moments, at a slant to intention,” Eaves notes in a particularly lovely phrase, “are what make art surprising and life worth living.” Or, as Critchley wonders: “Wouldn’t you like to be lifted up and out of yourself into a sheer feeling of aliveness?” Go on, then. It certainly sounds tempting.The Point of Distraction by Will Eaves TLS Books £9.99, 80 pagesOn Mysticism: The Experience of Ecstasy by Simon Critchley Profile £18.99, 336 pagesJoin our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and subscribe to our podcast Life & Art wherever you listen

رائح الآن

rewrite this title in Arabic In search of meaning — how to feed our spiritual hunger

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 خليجي 247. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.