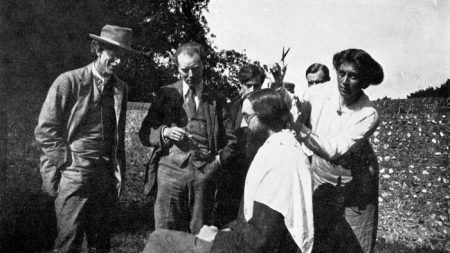

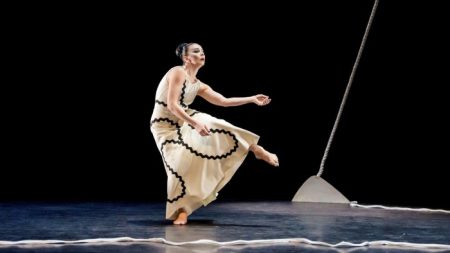

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic What could be more quintessentially English than William Morris’s interior designs? The sumptuous repeating patterns created by the chief founder of Britain’s 19th-century Arts and Crafts movement — popularised in his day by Morris & Co’s wallpapers and furnishing fabrics — have become global signifiers of an innately British style, copiously reproduced since his work exited copyright in the 1960s.Yet a show at the William Morris Gallery, his childhood home in Walthamstow, north-east London, which houses the largest collection of his work, shines light on a sometimes obscured inspiration. William Morris & Art from the Islamic World is the first exhibition to trace the profound influence of Iranian, Turkish and Syrian arts on the geometrically precise designs of the feted English poet, artist and radical socialist. Exploring their importance in his life and work, the show hints at wider exchanges between Victorian Britain and the Islamic world, while raising enduring questions about originality, imitation and appropriation.The gallery’s director, Hadrian Garrard, believes Morris’s Islamic world sources are not sufficiently acknowledged. “For us,” he tells me, “it matters in a community where 20 per cent of residents identify as Muslim,” as well as being “important to rethink what we mean by Britishness and Englishness.” A corner of the permanent collection already touches on the subject. But, he adds, “we’re threading it into the rehang” planned for the public gallery’s 75th anniversary next year, which will also bring an exhibition on the spread of his designs, Morris Mania.Morris (1834-1896) was less explicit about his Islamic sources than artist friends such as William De Morgan (whose “Lion Rampant” tile panel of 1888-98 appears in an upstairs room). Yet their influence can be inferred from his lectures, his work steering acquisitions for the South Kensington Museum (later renamed the V&A) and from what he owned. “Once you put them side by side, you can’t not see it,” Garrard says.Even with its muted browns, the staggered blooms in Morris’s machine-woven carpet “Tulip and Lily” (1875) mirror the alternating red and blue tulip heads of a 17th-century Ottoman quilt fragment he owned. The composition of his block-printed wallpaper “Wild Tulip” (1884), in white on salmon pink, unmistakably echoes the blue, green and red profusion of carnations and tulips on a 17th-century plate from Iznik, Turkey, also in his collection. Turkish wild tulips were smaller than the Dutch cultivars of tulip mania, appearing budlike in his delicate design.Such objects from Morris’s cherished personal collection are reunited here for the first time since his death — from his house-museums in England, and public collections such as the V&A and Birmingham Museums Trust. They range from illustrated volumes of the Iranian epic poem the Shahnameh and the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam (from which Morris read to his family) to three gorgeous 16th-century Ottoman-Syrian vine trellis tiles in indigo, turquoise and green.Though Morris never ventured east of Italy, he began to collect west Asian art in his thirties from dealers and auctions, studying fragments to discern technique. He was “not a collector, but a magpie”, the show’s co-curator, Rowan Bain, tells me. He trawled everything that caught his eye, from tourist tat to masterpieces. All 60 works on show were owned or made by Morris or his daughter, May, an embroidery artist who travelled to Egypt and Morocco, and became one of her father’s first curators.Morris, along with John Ruskin and Augustus Pugin, was part of a 19th-century backlash against the industrial revolution’s machine-age mass production. His life-long pursuit of a “beautiful house” entailed vegetal and floral designs, often with fauna, in which “nature was tamed into well-ordered patterns for the home,” Bain writes in the accompanying book Tulips & Peacocks. As the architect Shahed Saleem notes in the book, an “English aesthetic fantasy” idealised the Islamic world for its premodern links between artist, craft and nature.It was a time when Oriental artefacts were in demand, often in immersive, designed interiors (Leighton House in London’s Holland Park being a rare survivor today, and one Morris is assumed to have visited). Photographs of Kelmscott House, Morris’s Thameside home in Hammersmith, west London, show a 17th-century Safavid red-ground “Vase” carpet from Kerman in Iran rising up the dining room wall and ceiling like a canopy. “Eastern rugs were not made to be trod on with hobnailed boots,” Morris told puzzled visitors, while May described the carpeted “Eastern Wall”, with its twin metalwork peacocks, as having “more than a touch of the Thousand and One Nights”.The c1870 Iranian peacocks in brass and turquoise are in the show, along with Morris’s 17th-century Iranian lampstand with cheetahs and gazelles, and a 19th-century Iranian Qajar steel casket with gilt decoration. His “Flower Garden” (1879), suggesting the “beauties of inlaid metal”, according to an 1883 catalogue, subtly translates the effect of such metal inlay into woven silk. Alluding to Islamic Spain, the furnishing fabric “Granada” (1884) — so complex it was never commercially produced — combined inspirations from Italian and Ottoman velvets in its pomegranates and almond-shaped buds.Morris’s “biggest influences came from Turkish art”, says co-curator Qaisra M Khan, who believes such connections were more apparent in his lifetime, but faded from view from the 1910s. But he viewed Persian art as a pinnacle. “To us pattern designers, Persia has become a holy land [where] our art was perfected,” spreading “east and west”, Morris wrote for an 1879 lecture.India — another huge influence — is not in this show, but in an 1877 speech, “An Unjust War”, Morris, as treasurer of the Eastern Question Association, argued against being dragged into Turkey’s war against Russia simply to protect British interests. “He saw India as compromised by industrialisation,” Bain says, and was opposed to imperialism, though, “as a wealthy businessman, he profited from the import of raw materials, such as cotton and dyes.” Despite scrutiny now of “cultural appropriation”, Morris’s genuine appreciation of Islamic arts in an era that relegated not just decorative arts, but whole cultures, as inferior, anticipated today’s attitudes.So are Morris’s designs still original? He urged close study, not imitation. For him, the meaning behind patterns was crucial, and those perfect designers “meant to tell us how the flowers grew in the gardens of Damascus . . . or how the tulips shone among the grass in the Mid-Persian valley”. Learning from, and adapting, west Asian genius in repeating form and colour enabled him to capture England’s cottage gardens and hedgerows, imbuing his unique designs with their own palette, sensibility and meaning.If anything, this intriguing show bears out the view of Edward Said, author of Orientalism (1978), on how inextricably connected the world is. “There are no insulated cultures or civilisations,” Said wrote. “The more insistent we are on separation, the more inaccurate we are about ourselves and others.”Would Morris, who made no attempt to hide his sources, have favoured openness about the borrowings behind his prolific legacy? The choice of a tulip-motif, 16th-century Ottoman velvet as his funeral pall — never exhibited until now — might offer a clue.To March 9, wmgallery.org.uk

rewrite this title in Arabic How William Morris was inspired by Islamic arts — exhibition review

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 خليجي 247. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.