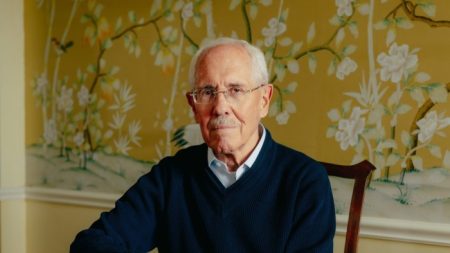

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Guan Hu is not a man of many words. Black Dog, which he directed and which won the Un Certain Regard prize at Cannes this year, is the same. The story’s emotional centre is manifested in the silent exchanges between a man and his dog and the obliterating force of the Gobi desert landscape, where canines rule. “The film is built from silence,” Guan says, “the possibility of a mysterious channel of non-linguistic communication between humans and dogs.”Among the undulating charcoal sand dunes, time feels like it has stopped. Wide shots capture humans and animals shuffling together across the desert looking like insects. They wander aimlessly through a ghost town that appears like a ruin from another time. Dogs appear everywhere, from the top of dunes to the town’s empty streets to the crevices of abandoned buildings. By placing humans and animals on an equal scale, Black Dog examines the “animality within humans”, Guan says. “From the beginning, we decided on a principle of ‘non-interference’, an observational mode. We didn’t want to interfere with life as it is. Our perspective is that human fate is insignificant and small in the vastness of nature and the Gobi desert.”Guan comes from the “Sixth Generation” of Chinese filmmakers alongside international festival favourites Jia Zhangke and Wang Xiaoshuai. Having emerged in the early 1990s, the group is characterised by its distinct realist style and focus on people on the margins of China’s rapidly changing society.Unlike his contemporaries, Guan is harder to define: before turning to this art-house feature, he mostly made commercial cinema that examined China’s military history with a more patriotic undertone, including his hit war drama The Eight Hundred, the nation’s top-grossing film of 2020. However, in his early career, he made more independent features such as his debut Dirt, about the Beijing rock scene. “Now, with Black Dog, I hope to return to listening to my inner self, to go back to that spirit that defined my early career,” he says. “So, this film is quite intimate in that sense.”Growing up with a theatre actress mother and a film actor father, Guan watched everything and was a child of the Beijing studios — “Everything from auteur European cinema to national hits . . . I am particularly influenced by Stanley Kubrick and Alan Parker. They are completely original and don’t belong to any single genre.”Similarly, Black Dog evades easy categorisation. Structured as a hybrid noir-Western, the film shows taciturn loner Lang (Eddie Peng) returning home to confront the ghosts of his past. It’s 2008; Lang has been serving a sentence for manslaughter. He is not exactly welcomed back with warmth — his dad now lives at the dilapidated local zoo, while Lang is sought after by “Butcher” Hu (Hu Xiaoguang), whose nephew he is said to have killed.Rather than facing a gun-toting mob in classic noir style, though, Lang’s enemy is a snake-venom vendor; instead of a classic femme fatale, Lang’s key relationship is with aggressive greyhound, Xiao Xin. “We wanted to choose a rather strange dog — one that’s not easy to tame,” Guan says. Similarly, when casting Peng for the role, “he didn’t seem like the soft, handsome characters he played before, so I was interested in showcasing that wolf-like toughness within him. Lang’s character is largely silent, which is crucial. Coming out of prison, many ex-inmates don’t like to speak much — it’s like a rejection of the society they are returning to.”Yet this is no man-and-dog best friend film: Black Dog refuses to fawn over the domestication of the beast. “When Lang encounters the dog, it’s not a pet, it’s a character,” Guan says. “These people and these dogs are outside the mainstream, lonely, desolate and unable to keep up with the times. What about these people? I think films have the responsibility to focus on them.” In order to establish the relationship between Peng and Xiao Xin, they spent two months on set rehearsing every scene. “Xiao Xin and Eddie were inseparable, even sleeping together,” Guan says. “Eventually, Eddie adopted Xin.”Guan’s film, shot in the city of Yumen, is structured by a sense of absence — an anti-city symphony of sorts. Shots are frequently set within dilapidated buildings or outside the empty cages of the local zoo, which, Guan says, “we actually found like that. So many buildings were completely abandoned. These north-western towns were once very prosperous, but they declined when their resources were exhausted. You can see these well-built facilities like hospitals and restaurants — but there are no people inside. The buildings tell a story of Chinese contemporary society.”The camera frequently pans past a mural for the upcoming Olympics, already fading. “I wanted to set it in 2008 because it’s one of the most important years for China. It’s the year of our greatest pride, but also the most suffering. There are some people whose lives were forgotten that we will never see.” Despite its subject, the film avoids a stark realism; the director opts instead for what he describes as a “surreal naturalism”. “To make this film, we needed a metaphorical system,” he says. “Beneath this story, there must be elements of fantasy and transcendence.” As well as dogs, the film is also populated by dozens of snakes, a tiger at the zoo and a wolf glimpsed on the horizon, which “plays into their mutual isolation and alienation from the world”. While we’re speaking, Liang Jing, Guan’s wife and producer, pops on to the call: “There are always animals in Guan Hu’s films. There was a cow, puffer fish and a horse. Dogs are relatively easier to direct.” Does he not struggle with the lack of control when filming animals? Guan shrugs. “If you don’t get the shot, you keep trying. Lang and Xiao Xin’s first meeting had to happen in a one-shot sequence. We filmed this shot for 20 days. Still, it was a particularly joyful shoot. It felt like the gods were helping me. There was even a sandstorm that blew over a car. But we just kept filming.”Despite the fragility of man and dog throughout the film, it is a testament to Guan that even this smallness can contain such immense power. In the final shot, we linger on a close-up of Peng’s face; his presence “is about this doubleness — of both his insignificance in this desert,” Guan says, “but also how he is our complete filmic universe.”‘Black Dog’ is released in UK cinemas on August 30Find out about our latest stories first — follow FTWeekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen

rewrite this title in Arabic Director Guan Hu: ‘2008 was the year of China’s greatest pride, but also the most suffering’

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 خليجي 247. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.