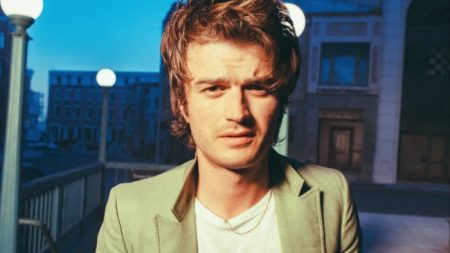

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic If he had the time, which he absolutely doesn’t, Daniel Brix Hesselager would have designed and made every chair and table in his home on the edge of the woods in Aarhus, on the east coast of Denmark. “I studied furniture design at college,” he says. “But now I’m what you’d call . . . a theoretic craftsman.”But while Rains, his cult weatherproof clothing brand whose fans include Dutch footballer Virgil van Dijk and British rapper Central Cee, isn’t anything close to tables and chairs, he considers it to be adjacent. “I always saw the brand as a universe inhabited by products that could [either] be interiors-based, or the clothes we make now. And there’s a lot of hardware involved in creating Rains products.”He met his business partner and co-founder Philip Lotko while studying at the Teko Design School in Herning. After an aborted attempt at running a streetwear brand, they came up with the concept for a waterproof apparel line because, as he says, “it rains a lot in Denmark”. They launched in 2012. The minimalist, mostly monochrome nature of the brand has made it a success internationally, with 2023 revenues of DKr627.7mn (£69.9mn) and 30 stores across four continents, in cities from New York to Shanghai. It started out primarily with jackets and capes, at price points around £100, and has expanded into bags, thermal parkas and accessories. The aesthetic is reflected in the interior of Brix Hesselager’s home, where he moved with his partner Line, a teacher, and three children, aged six, nine and 11, a year after launching the business. The transformation of his home, like his business, was based on a single strong idea: here, Brix Hesselager was looking for something with the potential to make a statement and would allow him to flex his creative muscles on a significant scale. “It’s what I’d call ‘historical architecture’, because it’s a mix of so many different styles, from Roman to Dutch,” he says. The house was originally built by a wealthy brewer in the 19th century as a summer residence. “He was really the first person to move to the area and build such a grand place. Then other business people followed.” The building was left empty for around a century before it was taken over by the town and used as a community hall. “It looked institutional,” he says. “The ways in which it had been reconfigured damaged it a lot. We brought an architect back in to reshape it, focusing it around three main living room spaces, and moved the main entrance from the south of the building, to [maximise] where most light would get in, and for a new sense of symmetry.”Brix Hesselager has stacks of photographs of the house from when the brewer lived here — it was full of heavy, ornate brown furniture and chintz textiles. The home had been christened “Krathuset” and was a flamboyant display of industrial wealth. The exterior broadly still looks as it did when it was built in 1871, but the interior furnishings, finishings and reconsidered proportions are arrestingly contemporary. There’s a futuristic Blossi chandelier consisting of six saucer shapes attached to a powder-coated metal circle in the living room, created by Danish designer Sofie Refer for Nuura — one of several dazzling, handblown light fittings that illuminate the place after it gets dark in mid-afternoon, during the short days of winter.“I immediately loved the house because it’s so close to the forest — what we’d call a skov hus — and the sea,” says Brix Hesselager, who moved to Aarhus for proximity to the Rains studio. “I knew it was far too big for what we actually needed. But I loved the idea of bringing something so historic back to life, in a totally contemporary way.”Although eclectic, the place is still, largely, a paradigm of modern Danish design, with clean lines, muted greens and greys, and furniture from the Scandi canon. It’s as precise and considered as a film set; exactly where you’d imagine a successful young Danish fashion entrepreneur to live. Up in an attic space, by a wood-burning stove, is Finn Juhl’s 1949 Chieftain Chair in walnut and black leather. At the bottom of the staircase is Juhl’s curvaceous 46 Sofa. Around the marble dinner table — a set of brown leather Series 7 chairs by Arne Jacobsen for Fritz Hansen from the mid 1950s. The colour palette is a visual echo of the nearby oak-filled woodlands, while the graphic split-square shapes of the oak flooring in the hallway are a recreation of the 19th-century original, as well as a reference to what’s still flourishing outside. Delft blue is painted on the walls around the stairs, as well as on replicas of two 1820s engravings by Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen from the original interior, one featuring a winged figure scattering flowers from the sky; the other with an angel carrying two children that represent sleep and death. “I find these works interesting, the juxtaposition of life and death,” he says. “I wanted to make them feel more contemporary by painting them the same blue as the rest of the space.”It’s as precise and considered as a film set; exactly where you’d imagine a successful young Danish fashion entrepreneur to liveThere are some decidedly un-Danish visual twists to the house, too. “I think there’s a lot of southern European style evident in the building,” says Brix Hesselager. The architecture is Italian-inspired and ornate, and the family frequently brings back pieces by street artists from their holidays in Barcelona. On a wall behind a Muller van Severen Duo Seat — part chair, part chaise, with a minimal hammock construction on a metal frame — there’s a brightly coloured painting by Barcelona-based artist Sam Grant of a woman in green jeans holding a yellow-and-pink striped ceramic. Brix Hesselager acquired it from urban art gallery Base Elements in the city’s Gothic Quarter.The lozenge-shaped dining table is a swirl of sand and coffee-coloured marble, a palette echoed by the sofa — a 1970 design by Mario Marenco from Arflex. It’s low to the floor, soft and inviting, wrapping around the coffee table in a giant L-shape. It’s practical, too. “This is where we gather most as a family,” he says. “It’s great to chill out, but also fun for the kids because they can jump all over it, like a playground. We spent a lot of time thinking about what furniture needed to be child-friendly, but the sofa is also like a cool sculpture as much as it is functional.” There is also actual sculpture nearby: a giant all-white work that dominates one wall. It looks like a cast of a rock face. It’s by Jacob Egeberg, a Copenhagen-based artist who has created several installations for Rains stores. The sculpture is made by 3D scanning small models and then carving them by CNC router. When the house was built, the technology behind Egeberg’s sculpture would have been unimaginable. Today, Aarhus is the second-largest city in Denmark and a hub for culture and design. It’s ironic that what was once a summer house now really comes into its own in winter, when the surrounding forest and grounds are heavy with snow. One of the main changes in the configuration of the house was moving the kitchen, which was originally in the basement. Today, it takes over a large space on the ground floor with views out to the south-east; the sun floods the room every morning. When natural daylight is in short supply in the Scandinavian winter, every beam counts. And like his brand’s mission of creating garments for people to go about their business as normal in a downpour, so Brix Hesselager has created a home that’s bright when it’s dark, and warm when it’s cold.Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ft_houseandhome on Instagram

rewrite this title in Arabic Daniel Brix Hesselager: ‘I loved bringing something so historic back to life’

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 خليجي 247. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.