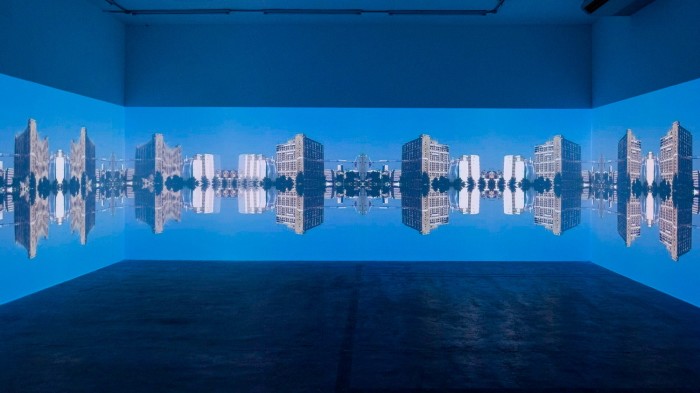

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Amid war and other overwhelming catastrophes, businesses in Beirut have struggled to operate in recent years. Now, Lebanon’s new and long-awaited president, Joseph Aoun, and a tentative peace process across the wider Middle East are giving its art galleries some optimism for the future. “There is, at last, a mini glimpse of hope,” says Joumana Asseily, owner and founder of Beirut’s Marfa’ Projects. It has been a long time coming. In 2019, Lebanon’s civic uprisings against corruption, known as its October revolution, brought down the government. In the years since, the country has been plunged into economic depression. Woes have included a liquidity crunch that led to a default on foreign debt, hyperinflation and the collapse of the Lebanese pound, which sits today at nearly L£90,000 against the dollar (prior to late 2019, this was about L£1,500). Living conditions have plummeted accordingly and in 2024, the World Bank reported that Lebanon’s poverty had tripled to 44 per cent of its population. “We haven’t had electricity or water or state schools. We’ve had nothing, we have not been a country,” says the Beirut and Hamburg gallerist Andrée Sfeir-Semler of Lebanon’s recent years.Other crises have punctuated the economic demise. In February 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic officially reached Lebanon, although Sfeir-Semler characterises this as “actually the smallest thing that happened to us”. Later that year, thousands of tonnes of ammonium nitrate, stored in the port of Beirut, exploded and killed more than 200 people while also devastating much of the city. More recently, the war between Israel and Hamas sparked cross-border fighting between Israel and the Lebanese militants, Hizbollah, escalating to deadly Israeli air strikes that included central Beirut.Business owners have had more than their fair share of interruption. Marfa’ Projects has been closed for a total of 15 months since October 2019, including nine following the 2020 chemical explosion, during which time Asseily had to rebuild her gutted gallery. (Marfa’ means port in Arabic and the space is named after its location, less than half a mile from the port blast.)Art fairs and biennials around the world have helped keep business going and offer her mostly Lebanese artists some visibility, Asseily says, while some of the online and collaborative initiatives that developed out of the Covid-19 lockdowns are still proving effective. The gallery remained operational during the war, she adds, albeit only “on calmer days” and “by appointment only”. Marfa’ Projects is currently showing in London, taking over Sylvia Kouvali’s gallery in Mayfair as part of the month-long Condo gallery-sharing project. Here, works include an installation by Ahmad Ghossein incorporating four totemic wooden beams wrapped in Lebanese pound notes to represent the artist’s savings. These were worth the equivalent of $13,520 in 2019, now they amount to $225, the gallery says. The work, completed by Ghossein’s actual bank statement, is called “How to make your money sell” (2023), and is offered for the original $13,520 value of his savings. Other artists are keen to investigate Lebanon’s longer history. On the opposite wall to Ghossein’s bank statement are small, delicately painted works by Lamia Joreige, part of her Uncertain Times series, poignant reflections based on the diary of a 20th-century Ottoman soldier, stationed in Jerusalem (the exhibition runs until February 15).Back in Beirut, Sfeir-Semler has reopened a two-venue exhibition by one of its star artists, Walid Raad, prematurely closed during the heat of the war. Among the works in its flagship gallery in the capital’s Karantina neighbourhood — also rebuilt after the 2020 explosion — are immersive projections of waterfalls, looming over paper figurines of world leaders (including Yasser Arafat and Margaret Thatcher). Sfeir-Semler’s newer downtown space has Raad’s 2024 installation based on the 1983-84 heavy bombardment of Lebanon by the USS New Jersey, including a shrouded Volkswagen Beetle (many Lebanese referred to the battleship’s shells as “flying Volkswagens”). The response to the show, which runs until March 28, has been “enormous”, Sfeir-Semler says — “standing room only” on recent nights, following the appointment of a new president. “People had stopped for so long and were waiting for life to restart.”She and others believe in the power of Beirut’s still nascent contemporary art scene to effect change. “Art is vital in the broader resistance movement and key to collective liberation,” says Ibrahim Nehme, director of the not-for-profit Beirut Art Center. His space shut when the fighting intensified last September and reopens on February 6, “after a rethink about our strategy for the next few years, in view of all that the country has gone through,” he says. Fundraising is “high on the list”, he says, though he believes “this will come if you have a solid programme”. The opening exhibition is of the poet-artist Hussein Nassereddine, and includes one of his ornamental water features made from paper, “A Few Decent Ways to Drown” (2023).Private donors, the principal source of arts funding in Beirut, have been challenged by the financial downturn. But for those with the funds, there are now a few more contemporary art initiatives for them to choose from, Nehme says. There is “a shift in the collective energy”, he adds, albeit a fragile one. “There is still a lot of tension and uncertainty, but a renewed sense of promise that could help attract new investment to the city,” he says. Energy around the wider Gulf region is playing its part, Sfeir-Semler says, citing support from institutions such as the Louvre Abu Dhabi and the forthcoming Sharjah Biennial (which opens on February 6). Gallery artist Rayyane Tabet, born in the Lebanese town of Ashqout, was the winner of the first AlMusalla Prize for architecture with an eye-catching, loom-like modular structure, designed with East Architecture Studio and the engineers AKT II, now on view at the Islamic Arts Biennale that opened in Jeddah this week.Ultimately though, it seems to be the efforts of Beirut’s individuals fighting for its cultural causes that will make the difference. “Immediately after the [2020] blast, I knew I would reopen the gallery, there was no other way to support the region’s artists,” Asseily says. Galleries in other destroyed cities — notably Kyiv in Ukraine — have shown similar stamina, although Sfeir-Semler says that there is a distinctly Lebanese flavour to Beirut’s persistence: “It’s like that game [whack-a-mole]. You knock us down, and we stand up again. In Lebanon, as soon as we can breathe, we start to work, and then to party.”Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning

rewrite this title in Arabic Beirut has suffered endless catastrophes — its art galleries offer a glimmer of hope

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 خليجي 247. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.