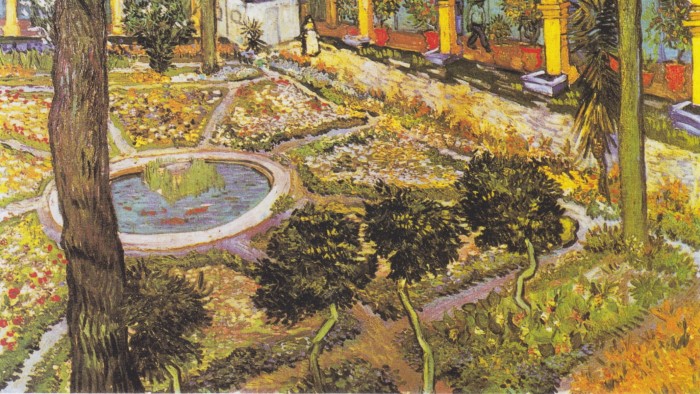

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Our responses to gardens depend on more than weather, soil and the plants we place in them. They also depend on our moods. Like light, they change with time and circumstances. We are not cameras. I have been musing on this mutability from two angles, the post-Christmas weather and a magnificent exhibition in London’s National Gallery. Each puts viewers’ moods at the heart of how gardens are perceived.If you dream of a white Christmas, in modern Britain the reality is a grey one. I try, but fail, to enjoy gardens while dark clouds, rain and gloom propel them into the new year. Just before Christmas a woman from the Orkney Islands described on BBC radio how darkness begins to fall there in mid-afternoon. She considered it a challenge and a test of character. She lifted my mood. Even so, in the grey days after Christmas, I did not try to appreciate flowers in the dankness outdoors.On January 2 the light changed and moods changed with it. Clear sunny weather made scrutinising gardens a pleasure. At home I found flowers on the dark blue Gentiana acaulis Krumrey, a gentian which had lost the time of year: its usual flowery season is April. In Oxford there were late flowers on our fine red rose, the single-petalled Bengal Crimson, whose shapely buds had first opened in May. Lavender-blue flowers on Iris unguicularis were less of a surprise as it is a regular flowerer in winter. So is Wintersweet, that spreading shrub from China. It was covered with scented flowers of translucent pale yellow.A day later, a frost at night preceded yet more sunny crispness. The frost damaged the roses, but not my mood. The flowers of Wintersweet are frost-proof. Cold weather intensifies their scent, making it superior to Chanel’s famous No 5. Forget the Orkney Islands, I thought, as sunlight revitalised gardens in my mind.In London the National Gallery’s superb exhibition on a phase in Van Gogh’s life opens similar vistas (until January 19). The beginning and end of my past 12 months have been linked by his art as if in a ring. Last January, I admired the fine show in Paris’s Musée d’Orsay of his works in the last months of his life. Flowers, trees and gardens were subjects of many of the best. In London, the current show covers the two previous years. It is entitled rather tenuously Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers, but gardens and flowers are prominent in it too.Its second room is labelled “The Garden: Poetic Interpretations”. In and around Arles, Van Gogh painted parks, gardens and wild fields, presenting them with yellow, pink and orange colours, which were indeed an interpretation. His paths could be blue and his fields of poppies were rearranged to suit his eye in his studio. Like no other artist, he conveys swirling movement in fields and trees. He changes what we see in them. Van Gogh responded to winter in a way which strikes an immediate chord with us this year. His letters survive, an unmissable complement for his art at any one time. Van Gogh was as alert as any of us to the changes that sunlight’s clarity brings to our responses. In February 1888, he left Paris for Provence and later described himself on leaving as “very, very upset, quite ill and almost an alcoholic through overdoing it”. As he headed south through France, he recalls how he looked out of the train window to see “if it was like Japan yet”. He was fascinated by Japanese art and the “simplification of colour in the Japanese manner”. If the light stayed clear in Provence, he wrote, “it would be better than the painters’ paradise: it would be Japan altogether,” his imaginary utopia. What he saw was already interpreted through personal screening. In the south of France, he remarked, he could make out the colour of things at an hour’s distance, the olive trees, the green grass, the “pink-lilac” of ploughed land. In sunlight we still can.In Arles, he rented the yellow house, which his art has now made world- famous. As usual, his brother Theo sent him money. Van Gogh’s letters are cardinal statements about making a house into a home while using the smallest of budgets. His paintings of it are now worth a fortune. In it he waited eagerly for his fellow artist Gauguin to visit. He then painted his vivid pictures of sunflowers, one of which Gauguin really liked, but the visit ended in disputes and disaster. Van Gogh, mentally disturbed, cut off his own ear, wrapped it in newspaper and is said to have taken it to a nearby brothel. Gauguin promptly left for Paris.Van Gogh was sent to a hospital in Arles and then presented himself at an asylum, formerly a convent, at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, about 15 miles to the north-east. In both places he painted flowers and gardens: they are stars of the London show. The show’s curator tries to polarise the results, presenting them as hopeful in Arles but despondent in Saint-Rémy. I disagree, as his letters at the time attest complexity.Van Gogh responded to winter in a way which strikes an immediate chord with us this year; alert to the changes that sunlight’s clarity brings to our responsesIn the Arles hospital, Van Gogh wrote how work distracted his melancholy amid his bouts of mental illness. Poignantly, he kept citing to himself Voltaire’s Pangloss and his philosophy that all is for the best in the best of all possible worlds. It is so touching: what we now admire is the result of these hard-working interludes. In May 1889 he finished a fine painting of the garden in the hospital’s courtyard from a gallery above. He wrote about its beds of forget-me-nots, anemones, buttercups and much else. Orange trees and oleanders, he noted, surrounded it. Nonetheless, “three black, sad tree trunks,” he wrote, “cross it like snakes” and “four large sad dark box bushes” stand in the foreground. In the Arles hospital, sadness was already present in his art.In Saint-Rémy, he battled on, painting flowers despite bouts of extreme mental turbulence. The hospital’s garden was overgrown, but Van Gogh found a rose bush in it and painted it heavy with white flowers. The painting gives no hint of his own inner mood. It applies thick paint with swirls which excel the master artist of roses, serene Henri Fantin-Latour.Roses, now fading, also feature in his picture of the Saint-Rémy garden itself. It contained a tree struck by lightning. Deliberately, he used green saddened with grey and black defining lines. In a letter he related this shattered tree, the last rose of the year and these dark colours to a “little of the anxiety” which his fellow “companions in misfortune” felt when “seeing red”. Yet, at the same time he had painted a field of new wheat, using violet and green-yellow under sun. In it, he “tried to express calm, a great peace”. He succeeded.There is a direct link between our moods and our enjoyment of a garden. The link between the contents of a work of art and the artist’s own mood is more oblique. Since Christmas, I have relearnt these lessons. So across the years I send Van Gogh one of those “handshakes in thought” with which he concluded letters, including his last one to his brother, just before he shot himself, tragically, in summer 1890.“Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers”; National Gallery, London Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ft_houseandhome on Instagram

rewrite this title in Arabic A sunlit winter planted hope and despair in Van Gogh’s Provençal gardens

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 خليجي 247. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.