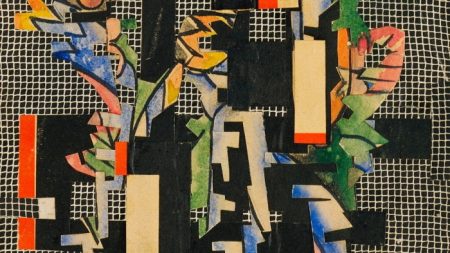

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic “Being in such a raw and wild landscape has given me the opportunity to focus and concentrate,” says Rupert Bevan. Twenty-six years ago, the one-time antiques restorer decided to move out of London with his young family. “We wanted to be in the countryside, at least two hours away from London,” he recalls. “It was almost eeny, meeny, miny, moe . . . and this is where we ended up: a very rural part of England, in the middle of nowhere, 20 minutes from the Welsh border, where I set up a workshop designing and making furniture.” Among the rolling hills of Shropshire, not far from the market town of Ludlow, Bevan’s eponymous business has grown from a small basement studio space into a run of Grade II-listed 17th-century barns, on the Downton Hall Estate in the village of Middleton. “We started off with four people; now we are about 34,” he says. “Moving here has given me the emotional and physical space that I never would have had in London.” It has also enabled him to tap into a rich seam of craftsmanship; he regularly works with a dozen or so local artisans — from metal forgers to specialist joiners. “It’s amazing how many talented makers there are,” says Bevan. “They’re people who prefer to be hidden away in the hills to get on with their craft, but if you look, you find them dotted around.” These include “one of the best woodcarvers in Europe”, Ron Hester, who lives in the sleepy town of Clun. He has crafted decorative elements for Windsor Castle, Shakespeare’s Globe and the Houses of Parliament. There’s also a specialist in scagliola: a material that looks like marble, wrought from plaster, pigment and glue, which became fashionable in Italy. “There are little nooks of creativity,” agrees Jess Wheeler, a designer-maker whose botanical homewares are handcrafted in bronze and plaster. Last year, she moved from north Wales to Devon, but she also has a workshop in Shropshire’s Sansaw Estate — a historic agricultural site near the town of Shrewsbury that today is part dairy farm, part business park. “All my team live in Shropshire and I’ve built a network of amazing makers and blacksmiths, which is part of the reason I couldn’t leave the area.” For some makers, however, the pull to the Midlands is familial. Rome-born Speronella Marsh moved to Shropshire in 2015 after her husband inherited a Victorian manor house, bought by his grandfather in the 1950s. Renovating the building — and specifically dressing its 94 windows — precipitated a new creative path, creating curtains from vintage sheets. “I’ve always collected them — don’t ask me why; I’ve wondered that myself for years,” she says. “But obviously not all the curtains in the house could be white, so I taught myself block-printing, through lots of trials and certainly lots of errors.” For each room she came up with a new design and they became the Home collection, which she prints to order — still on repurposed linens — in an old farm outbuilding. Scagliola artist Tom Kennedy is also based on a farm — “and I’m also a farmer, running 500 acres of farmland”, he says. He left London for Shropshire in 2011, moving into the arable farm that was run by his grandfather, then his father (who was also an antiques dealer). What was once a grain store is now his workshop. “It’s absolutely brilliant; you can make massive things in there,” he enthuses of the space that has seen the creation of 20ft dining tables and the odd giant egg, made to look like lapis lazuli. “I have this thing about obscure arts and crafts; I got really into stained glass for a while, and picture restoring, then settled on scagliola, probably because it was the most obscure of anything I’d come across.” But combining a bucolic setting with traditional craft techniques doesn’t mean the pieces being made have an old-world aesthetic. Both Wheeler and Marsh weave countryside motifs into their work with a contemporary twist, as big, bold prints of acorns and bronze wall lights cast from cabbages and fig leaves. And while Kennedy often works on classical commissions — including recent inlay work for a historic Bloomsbury town house being renovated by architect Thomas Croft — he also likes “to invent new kinds of marble and stone that never existed before: something completely wild”. A case in point is the bold, organic tabletops he has created for one interior designer, which resemble mottled, multicoloured granite from another planet. “I love craft and it frustrates me when people think of it as twee,” says Bevan, highlighting a common approach among his Shropshire network: “We’re all trying to make traditional craft relevant and modern — and financially viable.” His in-house workshops — for glass, metal, woodwork and upholstery — turn out a vast array of bespoke, handcrafted pieces, from mirrors to whole kitchens. On my visit, a decadently curved and mirrored Art Deco-style bar was being finished for a home in New England and a scallop-edged cupboard in textured, ebonised oak was destined for a villa on Lake Como. In recent years, Bevan and his team have also added made-to-order pieces to their offering: a collection that includes several dining tables and chairs, as well as needlepoint-topped bar stools and the mirrored Miami Cocktail Cabinet. Marsh, too, is branching out. Last year she launched her patterns as wallpapers, digitally printed to capture “that faded look of my block prints”. Next up is a range of by-the-roll fabrics, coming later this year. Both are printed locally. “I consider myself very lucky to live in the Midlands because of all the manufacturers that are here,” she says. In the 18th century, Shropshire was at the heart of the industrial revolution, when new iron-smelting processes pioneered in the village of Coalbrookdale were used to build steam engines and, famously, the world’s first iron bridge, spanning the River Severn. “Now it’s just tea shops,” says Kennedy of this erstwhile hotbed of technological change. Yet while the county’s new maker movement is much less seismic, and far smaller in scale, it still embodies a collective spirit.“Shropshire has become a place that creative people gravitate to,” says Kennedy, who is surrounded by a tight-knit network on his family farm. The wheat store next door is occupied by his brother, Archie Kennedy — a former prop-maker and model engineer for films including The Lord of the Rings trilogy, who now works in metal, making one-off commissions from gates to candlesticks. Opposite is Paul Kennedy (no relation to the brothers), who runs a bronze-casting foundry. “So between the three of us,” says Kennedy, “we can bounce ideas around, and help each other out.”Marsh and Bevan have become friends and sometime collaborators: “We meet once in a while and just talk creative,” Marsh says. Wheeler adds: “Everyone is collaborating and doing stuff together. It’s a lovely community.”Moving here has given me the emotional and physical space that I never would have had in LondonIn another converted barn, in the village of Leighton, Kate Elwell is helping to solidify this community with Master The Art — a space for creative workshops. Here, Wheeler demonstrates how to craft her brass plants and flowers and Marsh teaches block-printing. There are courses on making paper flowers (with local maker Charlotte Hepworth) and painting lampshades (with London-based Alvaro Picardo), while Elwell teaches paint finishes — “how to marble, malachite, tortoise-shell and lapis, and do amazing things to your house” — and her father, 86-year-old master gilder Roger Newton, teaches the craft that he first learnt in the 1950s at the revered design studio Colefax and Fowler. “I’m bringing the fun to Shropshire,” laughs Elwell. Her two-and-a-half-year-old enterprise already attracts a global clientele: “Somebody flew in from Palm Beach for our gilding course last week; a lady is coming from India to learn paint finishes in September.” She offers accommodation, too, on the top floor of her handsome red-brick home — a former school house, built in 1778, where the early 20th-century writer Mary Webb was born. “About 80 per cent of our customers come back; they just go, ‘Right, I want to do another course, and I want to add on another day and go around Shropshire, because I didn’t realise it was so amazing.’ It’s a bit undiscovered.”For those visiting, Kennedy sometimes does scagliola demonstrations with the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. “All of the museums around Ironbridge are fantastic,” he says. The undulating landscape is also a magnet for walkers, from the Wrekin — often cited as the inspiration for JRR Tolkien’s Lonely Mountain in The Lord of the Rings — to the Clee Hills. Wheeler is a fan of Shrewsbury, while Marsh extols the charms of Ludlow. “It’s really pretty; it’s got a great market, where there are basket weavers and wood carvers — the flea market twice a month is fantastic,” she says, highlighting vintage store Nina & Co and Harp Lane deli as favourites.Bevan suggests making Ludlow a base. “From there, you can go walking in the hills of Church Stretton, you can go into Herefordshire and to Hay-on-Wye and, if you’re very brave,” he laughs, “you can go directly west into Wales.”Find out about our latest stories first — follow @FTProperty on X or @ft_houseandhome on Instagram

rewrite this title in Arabic Shropshire’s daring, decadent and ‘completely wild’ crafts crowd

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 خليجي 247. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.