Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic

The remarkable thing about all of them was, you’d call and you’d make an appointment, even if it was to talk about the old days, and as soon as you sat down you’d realized how very wrong Fitzgerald had been. There most certainly are second acts in American lives. The CCNY Beavers, almost to a man, proved that in full.

“The shame, of course, is that because of the scandals, nobody ever talks about how good a basketball team we were. And let me tell you something, son: We were as good a basketball team as anyone has ever seen. People who saw us knew. People who played us knew. People talk about us, they talk about the fixers. OK, that’s fair. But, damn, we could play.”

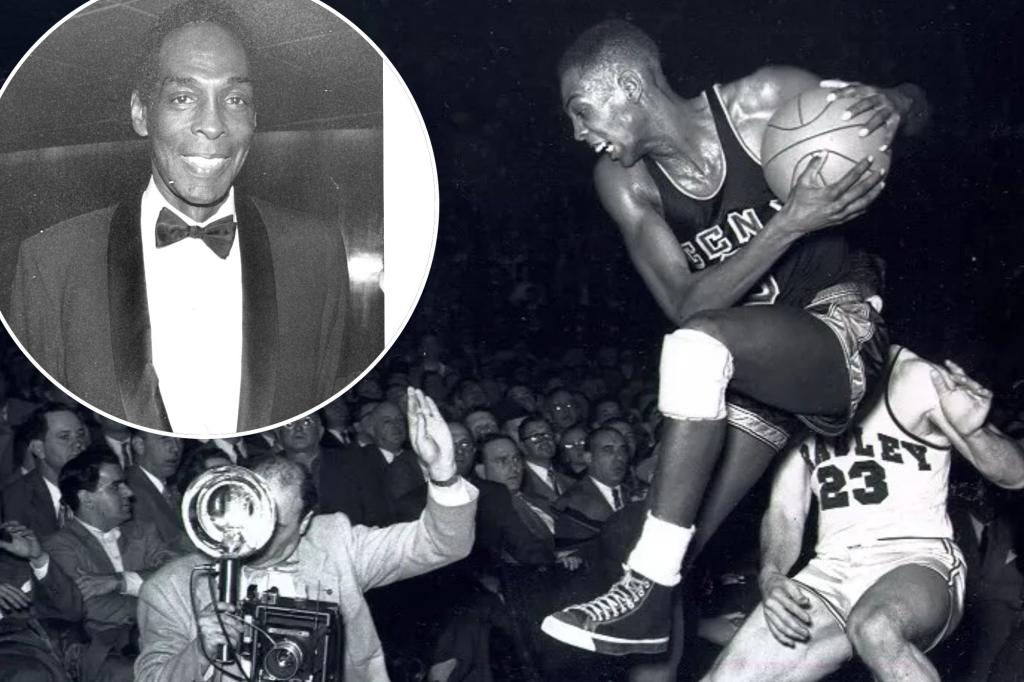

That was Al Roth, a foundational player on the 1950 Beavers team that did what no team had ever done before and no team will ever do again: They won the NCAA Tournament and the NIT in the same year, winning seven games at Madison Square Garden that thrilled their city and filled that smoky gym on 50th Street.

This was 2000. Roth was speaking in his office at Air-Zee Supply in Mahwah, N.J., the building-supplies company that made him a wealthy man. He was living proof you don’t have to be defined by the worst moment of your life, especially if that happens when you’re 19, 20, 21 years old.

Floyd Layne proved that more than any of them, and it’s good to remember that now, after Layne died Monday at age 94, the last of the double-champion Beavers to pass. On the eve of his induction to the New York Basketball Hall of Fame in 2003, Layne was the one who brought up the infamous part of his rich tapestry of a life. He never ran from it.

“What it did,” Layne said, “was force me at age 22 to put my feet on the ground and realize I was going to have to answer for my mistakes, but I didn’t have to be crippled by them.”

Floyd was one of the six CCNY players — and one of dozens at more than 90 schools — who were ensnared in the point-shaving scandals of 1951. He received $2,500 from gamblers. He used a portion of the money to buy his mother a new refrigerator and hid the rest in a flower pot, too scared and filled with guilt to touch it until the cops came to bring him away.

The scandal broke New York’s heart, and it nearly broke the sport of basketball in the city, but it never broke the athletes themselves, even though, while mostly spared prison time, they were immediately banned for life from the NBA, where most of them would’ve had 10-, 12-year careers.

Ed Roman became one of the most respected school psychologists in the New York City system. Irwin Dambrot became a dentist and invented a mouth guard for athletes. Herb Cohen, Roth, Norm Mager: They all became prosperous businessmen.

Layne spent the next 70 years of his life going another way. He was a star in the old Eastern League. He got a masters in education, became a public school teacher and a force in his Harlem community. In the ’60s he met a gifted kid named Nate Archibald, “Tiny” even then, and helped focus him on basketball, shield him from the city’s more sordid temptations.

“Floyd was a tremendous influence on my life,” Archibald said a few years ago. “He was responsible for keeping me off the streets. He ran a great basketball program and encouraged me to apply myself and to succeed in high school and go on to college.”

It was in 1974 when Layne’s story took a wonderfully cyclical turn. By then, CCNY had long given up the ghost as a big-time hoops power, was playing Division III and scuffling. Layne had spent a couple of years coaching Queensboro Community College. When the job opened, he was interested. When he was hired, it caused a sensation, not all of it positive.

“I had known his name because he was famous on campus because of how great a player he’d been, and because of the scandal,” says Mike Flynn, who was a junior on that first CCNY team. “But he never talked about any of that. He just wanted to teach us basketball. He wanted to share what he knew. He was calm, easy-going and that rubbed off on us.”

He also threw out the old, walk-it-up philosophy of previous coach Jack Kaminer, urged his players to run, and they took to him quickly. On Jan 28, 1976, the Beavers went into Rose Hill Gym and beat D-I Fordham, 61-52, easily the school’s biggest win in 26 years.

“I learned so much from him,” says Flynn, who hadn’t played high school ball at Van Buren but became a prominent Beaver. “He had a way about him. He was just a good, good man.”

Across the city Monday came similar testimonials from the thousands of kids Floyd Layne helped to become men.

“I hope,” he’d said in 2003, “that when the time comes, I’ll be remembered for the whole of my life and not small and regrettable part of it.”

He did that. The game, and the city, is a lesser place without him.