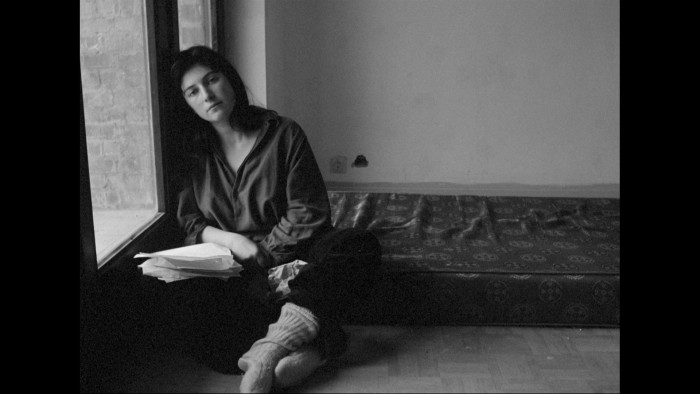

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic The first time I saw Chantal Akerman’s News from Home (1976), I was living in New York. That period of my life is now half-remembered, barely real. I couldn’t tell you what cinema I saw it in, but I do recall feeling profoundly moved. I don’t often confess to overt displays of emotion. The film was made when Akerman was living in the city, a time of freedom and exploration for her. (Describing her friendship with the cinematographer Babette Mangolte, she said, “She brought me to all the films, all the dance things, all the music things . . . She opened my mind, really. I was just a child when I arrived there.”) The film is simple: a voiceover of Akerman reading her mother’s letters accompanied by street scenes in New York. On my initial viewing, I thought that a lot of the poignancy came from her mother’s words, and it does. Akerman’s mother is frequently tired, ill, depressed. I recognised some of my own Irish mother in her too, when she writes, entirely unironically, “I’m very tired and look awful, but otherwise I’m fine.” Her mother’s life is one of unadventurous routine, full of dull visitations and small-town gossip. Her daughter’s world encompasses the whole, life-giving city. The distance between mother and daughter made me sad, a sadness that remained with me for days. It was an entirely adult realisation: parents frequently sacrifice so their children can make themselves over.When I next watched the film, also in a cinema in New York, I was struck by Akerman’s evasions. You can tell by her mother’s sometimes desperate replies — Akerman’s letters are unheard — that she is trying to pin her daughter down, her address, her friends. Who couldn’t recognise the youthful indifference to a mother’s inquisitions? The moment I remember weeping at was her mother’s line, “I dream about you and hope you’re happy” (this appears again and again on Instagram as a screenshot, stripped of all context, a floating image). A wish, a plea for a daughter who was very determined to set her own course. As if Akerman was ever searching for something like happiness.My third viewing of News from Home was in preparation for the BFI’s Akerman retrospective, which has just opened in London. This time, I only noticed how still and dignified it is. The camera barely moves. It looks at its subjects, and its subjects sometimes look back. On the subway where Akerman films, passers-by see the camera, look down, look away, step out of its gaze. You register their vulnerability; these people were totally unprepared to be filmed. All these strangers were aware of each other, living in their shared reality, and the camera was the intruder. In an interview in Artforum with the critic Gary Indiana, Akerman said she didn’t believe that character is always revealed through dialogue. “It’s also revealed by gesture, even from the back and from every side. When characters aren’t on the screen they can also be revealed.” In News from Home, more than any other film, I find this to be true. Even from the briefest glimpses of these strangers, how they hold themselves in public, I feel like I know them. Akerman pays attention to the most minor of details, a skill she used to powerful effect in her 1975 film Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, widely considered her masterpiece, as a widow, trapped in stultifying domesticity, slowly unravels.Lastly, I was struck in News from Home by how meaningful her mother’s correspondence is. The letters, with their suggestion of pain and loss, were worth keeping a record of. Attention is paid to each word. Every day I receive so much communication, most of which evaporates soon after I put down my phone. The title News from Home was refigured yet again when I reread Akerman’s memoir My Mother Laughs (it’s too odd and self-examining to call it an autobiography) when she writes, “But I don’t feel like I have a home or an elsewhere. There’s nowhere I feel at home.” The film’s title then becomes almost ironic, humorous. Her mother’s scraps of gossip could hardly be called news; there is no home.Chantal Akerman was born in Brussels in 1950 to parents who had survived the Holocaust. She was close to her mother, Nelly, throughout her life (My Mother Laughs is a document of their relationship, and of her mother’s illness and deterioration, as is her 2015 documentary No Home Movie). She made her first film, which she also starred in, when she was 18. Saute ma ville was a black-and-white short, thematically prefiguring Jeanne Dielman, about a young woman blowing up her kitchen and herself. Akerman dropped out of film college to make it. In interviews, she said she did different jobs to fund her art, working in bars, shops, as a coat-check girl and, my personal favourite, in a porn theatre box office, where she stole $4,000 to make Hotel Monterey and La chambre in 1972. Hotel Monterey is only 62 minutes yet manages to capture, with sustained shots, the strangeness and unreality of a hotel. Explaining this choice, she said, “I want people to lose themselves in the frame, and at the same time to be truly confronting the space.” While watching it, as in News from Home, time expands. It opens to you.In 1972, Akerman was living in New York, receiving letters from her mother, and being influenced by the likes of Jonas Mekas and Andy Warhol. But she always maintained the most influential film of her life was Jean-Luc Godard’s Pierrot le Fou (1965). On her return from New York, she made her first feature, Je Tu Ill Elle (1975), with its frank depiction of lesbian sex, and, again, starring herself. Then in 1975 came Jeanne Dielman.In 2022, ‘Jeanne Dielman’ was voted by critics as the greatest film of all timeIt has taken a long time for Jeanne Dielman’s reputation to grow. It culminated in 2022, when it was voted number one in Sight and Sound magazine’s 100 Greatest Films of All Time critics’ poll. Lists exist, and people love to get angry about them. The backlash was surprisingly strong. Paul Schrader, despite being a great admirer of the film, called the decision “a landmark of distorted woke reappraisal”. Why did people deem it undeserving? Akerman was only 24 when she made the film with a mostly female crew, and it has a running time of more than three hours. It’s a woman’s story and, by that, I mean it’s brutal and horrifying. Delphine Seyrig plays a widow whose inward desperation is controlled by discipline, her strict routine, the meals she painstakingly makes for her teenage son, the sex work she ritually partakes in to make ends meet. The viewer spends time in her kitchen, watches her peel potatoes, put on lipstick, complete her domestic chores to a near-hypnotic effect. It conveys the woman’s anguish and her changing mental state, in a number of minor ways: a crumpled shirt, her hair undone, a dropped pan leading to a denouement that is both terrifying and pitiful, an act of violence and madness.Jeanne Dielman can be read as a feminist film. Imagine showing it to a tradwife, those much written-about bastions of purity? It has a lesson, if that’s what you’re looking for, about the uneasy pacts women are often forced to make with men, and how total submission to the patriarchy can often lead to psychic torment. There is also another read. Both of Akerman’s parents were Holocaust survivors, and she must have always wondered how life continued after such an event. In this very manner: beds being made, dinners planned, bourgeois respectability upheld and never questioned. Jeanne Dielman was the first film I thought of when I watched Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest. Mostly, I was happy to see it at the top of the list because it confirmed to me that people want to be challenged. There is a sort of broad agreement right now that we only want hyperactive three-minute videos that reflect our views back to us. That suits people who wish to profit from our attention. To consider audiences only to be unthinking and incurious is deeply unfair, cruel and unambitious. As Jeanne Dielman is re-released into cinemas, I find the idea of people of all ages watching, and being touched by it, redemptive. I still like to believe that a film can change you.I think the reason Akerman’s work has grown in reputation is because she acknowledged the loneliness of life. Some of the worst moments in Jeanne Dielman come when Jeanne is briefly free of her chores, sitting alone, her face an agonising mask. This understanding is the relationship a viewer can have with a film when, as James Baldwin puts it, “you’re not at the mercy of a plot”. Akerman’s 1978 film Meetings with Anna is one of the loneliest films I’ve seen. The Akerman stand-in, Aurore Clément, travels around constantly on a publicity tour. The scenes I see again and again in my mind, like the looping actions in Jeanne Dielman, are the repetitive drawing of the hotel-room curtains, the closing out of the world. She got pleasure from her work, not from publicity. To produce such an incredibly defiant body of art at a young age proves that. Perhaps Akerman felt the focus, energy and determination that comes with being against time. She suffered from depression, and after a breakdown in her thirties, she described a loss of interest in an interview: “Previously, I had felt a kind of energy in life with moments of depression, of course — but I read constantly, was curious about everything. Then it was gone . . . The breakdown knocked me out.” As in News from Home, these few lines conceal a torrent of emotion. Chantal Akerman died by suicide in 2015, at the age of 65, not long after her mother’s death. I wonder how she, who was for so long an outsider, would feel about her inclusion in the canon.In preparation for the BFI’s season, I watched a 1984 Akerman short that I’d never seen before, J’ai faim, j’ai froid. In this electrifying film, which feels longer than its 12 minutes, two young female runaways wreak havoc on Paris. They leave cafés without paying, they walk into fancy restaurants and start singing, they kiss. One of them loses, in a moment of resolve, her virginity to an older man. They eat, they smoke, they inhale the city. The film is Chaplinesque — an inspiration for Akerman — and has a sweet, tender sense of humour, a quality of her work that was always underrated. I felt that this could be the inverse of what we see in News from Home, Akerman’s youthful adventures, wildness and giddiness. Akerman drew constantly on her private life but withheld too; she let her life and her work have its secrets. Discussing the ending of Jeanne Dielman she once said, “You don’t understand her. You will never. I hope you never will — that’s the strength of the film.” Nicole Flattery is an Irish novelist“Chantal Akerman: Adventures in Perception” is at BFI Southbank until March 30Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend Magazine on X and FT Weekend on Instagram

رائح الآن

rewrite this title in Arabic Chantal Akerman: why the late, great filmmaker is having a moment

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 خليجي 247. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.