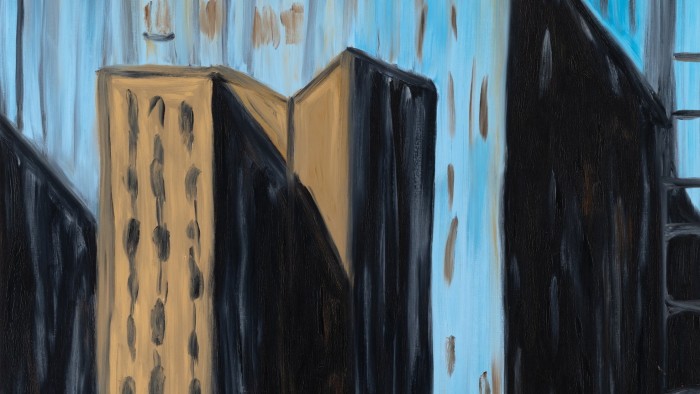

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Unlock the Editor’s Digest for freeRoula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.New York — the county, the city, the state of mind — haunts the work of Martha Diamond. The metropolis she paints, a place of blank windows, serried towers and unpeopled streets, looks simultaneously eternal and fleeting. Skyscrapers glower against the clouds like giant tombstones, or turn into pillars of fire reflecting the afternoon sun. Vertical lines bend, flat planes tilt, columns contort. Diamond fills her canvases with psychological drama just by recording the inherent moodiness of concrete and steel. She paints what she sees, unemotionally and from a distance, and yet the results wind up looking like the effusions of a tortured soul. It’s refreshing to come across her gritty scenes in the leafy Connecticut town of Ridgefield, an hour outside of Manhattan. An intoxicating survey at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum makes her cityscapes seem like dispatches from some distant expedition. The show, curated by Amy Smith-Stewart and Levi Prombaum, opens with an early untitled acrylic, a splash of strokes evoking Joan Mitchell’s abstract landscapes. Brushy squiggles of green suggest a mess of weeds beside a pond. Washes of light blue and a few darker curls hint at reflections of sky on water. The painting, from 1973, made an auspicious start to a long career, yet that lyrical mode and bucolic atmosphere dissipated quickly. It couldn’t survive in the city.Diamond was born in 1944 and mostly raised in Manhattan. From 1969 until her death in 2023 she lived in a loft on Bowery, enfolded in the island’s extreme rectilinear geometries. The streets were her terroir, buildings her topography and vegetation. She recalled childhood afternoons spent strolling in the Conservatory Gardens of Central Park with her father, who was a doctor at nearby Mt Sinai Hospital. But it wasn’t the plantings that stuck in her imagination so much as the looming apartment buildings and institutions arrayed along Fifth Avenue. For a little while, her family lived in Queens, and crossing the East River on the Queensboro Bridge meant heading straight for the great palisade of Midtown. (That view, F Scott Fitzgerald famously wrote, “is always the city seen for the first time, in its first wild promise of all the mystery and the beauty in the world”.)In 1966, she started working in the Museum of Modern Art’s film department, and the commute may have been the most meaningful part of the job. MoMA sits diagonally across West 53rd Street from Eero Saarinen’s CBS Building. “Black Rock,” as the tower was known, had opened two years earlier, almost shocking with its brawny simplicity and sinister carapace. “The dark dignity that appeals to architectural sophisticates puts off the public, which tends to reject it as funereal,” critic Ada Louise Huxtable wrote. It didn’t put off Diamond, who translated its cubist facets and brooding bulk into “Center City” (1982), a study in dark blues, deep blacks, and pale light. The exhibition culminates in a group of large canvases that read as portraits of buildings. “Green Cityscape” (1985) reaches back to her early nature scenes, with high-rises growing like tropical flora into a sultry and verdant world. A matrix of grey struts and braces along one edge of the canvas — a crane tower, perhaps — asserts the primacy of machinery in this urban jungle.Fifteen years later, Diamond was still cultivating her talent for finding the soul in steel and glass. In “Cityscape No 2” (2000), she fragments a vast reflective curtain wall into a diaphanous silver veil, its panes all aglitter like rhinestones on a gown.“On the surface, literally, my work resembles expressionist paintings,” she wrote: “the emphasis on looking at the paint itself, the undisguised brushwork, the obviousness of apparent distortion . . . ” Some buildings smoke and melt like candles, or shoot, half-cocked, towards the sky. In a few scenes, an errant window or a length of cornice stands in for a whole architectural assemblage. Her beefy brushstrokes, thick impasto and vibrant texture suggest, deceptively, that she might be projecting her inner world on to the physical one. But her goal, like Monet’s, was anti-expressionistic — to fashion an accurate, neutral record of optical sensations inflected by changing light and atmosphere. “I try to paint my perceptions rather than through emotion.” Diamond’s New York is empty of people but alive with echoes of other art. The teetering tower and explosive sky of “New York with Purple No 3” (2000) recalls Robert Delaunay’s fervid vistas of the Eiffel Tower from the turn of the last century. “John Street” (1989) builds up a deep, receding vista out of heavy walls, shafts and shadows, like a resurrected Edward Hopper.There’s an eerie, almost apocalyptic feeling to her city, like a collection of contemporary ruins. Its monumentality seems antique as well as modern, ephemeral as well as solid. In “World Trade”, she made two mammoth structures dematerialise at the stroke of a brush. The wind-strafed twin towers dissolve into vaporous verticals beneath a red horizon. All that is solid melts into air.The painting debuted at the 1989 Whitney Biennial, where the show’s curators characterised its subject as “spectral abstractions”. A dozen years later, the real monoliths were gone, replaced on each anniversary of the 9/11 attacks with two shafts of light that blur into mist and low-hanging clouds, like apparitions from a Martha Diamond vision.To May 18, thealdrich.org

رائح الآن

rewrite this title in Arabic How Martha Diamond painted New York’s soul — with beefy, brilliant brushstrokes

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 خليجي 247. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.