Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic From pristine wilderness to the open road, visions of the landscape have been crucial to the forging of America’s identity. When photographer Dawoud Bey wanted to make photographs about the country’s history, then, landscape was the province in which he chose to work. “Not the grandeur of it, not the Emersonian notion of its symbolism,” he says. “Something that’s very specific to that genre and generally not spoken about — the trauma of the African-American presence that sits just beneath the surface.”Trees, vaults of sky and the sliding surface of a deep river: Bey’s photographs utilise the established lexicon of landscape art. But his pictures are of places more resonant than the rest, where history is stoked into the earth and emits a kind of hum, places where “the leaves would sometimes start rustling, even when there was no wind”.The congress of beauty and violence can feel uncomfortable, appalling even, though that is partly the pointBey’s latest series, Stony the Road, brings to vivid life the narrow path beside the James River in Richmond, Virginia, on which upwards of 350,000 enslaved Africans were marched from their ships to holding pens in a sunken, swampy part of town known as Shockoe Bottom. In the 19th century, this “place of sighs”, as the abolitionist minister James B Simmons described it in 1895, was the hub from which the chattel trade spidered across the Deep South.Today, the site of its auction block, offices and whipping room lies beneath 10ft of fill dirt and the Richmond-Petersburg turnpike. “But the trail has not been covered up,” says Bey, “you can still walk on it. The ground still holds its shape and its memory.”A excerpt from Stony the Road will be shown by Sean Kelly Gallery at Art Basel Miami Beach this month, while the full work — 12 large and intensely tactile gelatin silver photographs and a film, “350,000” — makes its New York debut in the new year at the gallery’s premises in Chelsea, where I meet Bey on an uncommonly sultry day in early November, the temperature 25 degrees by mid-afternoon. Bey, who is 71 and among the most distinguished photographers in America, is in town from Chicago, where he is professor emeritus at Columbia College. He was born and raised in Queens, New York, however, and is pure Harlemite in his soul. His breakthrough work, a sequence of intensely physical black-and-white street portraits, was made there in 1979. He feels a particular connection to that neighbourhood, he tells me, both for its sociocultural significance in Black history and because it’s where his parents met and married. “When I’m in Harlem, I’m standing in the place that I remember, and the place that I’m in. For me, that’s the meaning of a place.” He recently bought a house there. “I’ve been away for many years, and now I’m working my way back.”The Richmond slave trail is not a landmark as such, or even well-known. Bey himself hadn’t heard of it until Valerie Cassel Oliver, curator at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, drew its three-mile route to his attention. The Museum went on to commission the work and showed the photographs first, last year.The series is part of a panoramic endeavour that maps early African American history from first steps in an unfamiliar land (Stony the Road), to the Louisiana plantations (In This Here Place, 2019) and the Ohio stages of the Underground Railroad (Night Coming Tenderly, Black, 2017). It is, Bey says, an “elegy in three movements”, though he is mulling over a fourth.Each of the series’ titles comes from Black culture, with which Bey intends his work to be in conversation: “Stony the road” is a line in James Weldon Johnson’s 1900 poem “Lift Every Voice and Sing”; “In this here place” is a phrase from Toni Morrison’s 1987 novel Beloved, and “Night coming tenderly, Black” is from Langston Hughes’s 1924 poem “Dream Variations”.You can understand why the landscape of Virginia felt potent to Bey. Slavery began here, at the inaptly named Point Comfort in 1619. The state is also where, in 1775, Governor Patrick Henry made a famous speech igniting the fight for independence. “All those words about freedom and democracy,” says Bey, his gentle voice rising abruptly to a roar, “‘Gimme liberty, or gimme death!’” The physiognomy of the trail is arresting, too: a shadow-chilled tree-tunnel that is forever curving away from you, its end forever out of reach. Its winding shape is in effect a scar, worn into the landscape by thousands of feet. The pictures are empty of those people, though suggestions of them drift out. Light breaks through the tree canopy only occasionally, to make Chantilly patterns on the ground, or spool silvery on the dark river’s tide. The congress of beauty and violence can feel uncomfortable, appalling even, though that is partly the point. “I made a formally beautiful object to make you stop and engage with it, and through that engagement come to the deeper question. ‘What exactly is this landscape? What happened here? Why is he here making photographs of that?’”Bey was not always a landscapist, nor even a photographer. He started out a jazz musician — accomplished enough to play Carnegie Hall — and still spends “as much time in jazz haunts as galleries and museums,” he tells me. His plans for the evening involve hitting the Village Vanguard, or a place uptown called Smoke. Jazz chimes with his ethos. “Music that doesn’t tell you ‘I love you’; that doesn’t tell you anything really, but is also telling you everything and moving you emotionally. That is what I want my work to do.”Periodically, he brings a sonic component to his photographs. “Not a soundtrack, not a song from that era, but imagining the sound of history,” he says. For “350,000”, that involved bringing leaves and soil from the Richmond slave trail into the Foley pit of a recording studio and layering it with the sounds of “breathing, of body smacking against body, the rhythm of scuffing feet”.Bey made the switch to photography around 1975, securing a solo show of his 35mm street pictures, Harlem, USA, at the neighbourhood’s Studio Museum in 1979. A half dozen of these dot the room in which we are talking. How does he feel about his old work? “They’re still good photographs,” he says. “They give the individuals a sense of physical presence, which is very important to me. It makes the picture less object, more experience — you can almost embrace yourself in them.” Bey’s Street Portraits (1988-91) are currently showing at the Denver Museum of Art.History became his primary focus about a decade ago, with a work that memorialised the child and teenage victims of a racially motivated killing spree in Birmingham, Alabama in September 1963. The diptychs of “The Birmingham Project” paired one portrait of a young person the same age as one of the victims, with another of an adult 50 years older — the victim’s age had she or he survived. “I wanted to understand what led to that moment,” says Bey, “this absolute refusal to let Black people occupy equal social space; what is the beginning of that narrative? And the beginning of that narrative is slavery.”Recently, Bey has come to see Stony the Road and its associated series as “an act of resistance”, he tells me. “Against attempts to erase this history by legislating away the teaching around it; to the ignorance and complacency that keeps more people dumbfounded — ‘How the hell did we get here? — when really, history explains all of it. It’s pretty straightforward. We got here, from there. There is very little that surprises me. It’s a pretty unbroken line.” ‘Stony the Road’, January 10-February 22, 2025 skny.com‘Street Portraits’, to May 11, denverartmuseum.org Sean Kelly, Booth F15, Art Basel Miami Beach, December 6-8 2024Find out about our latest stories first — follow FTWeekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen

رائح الآن

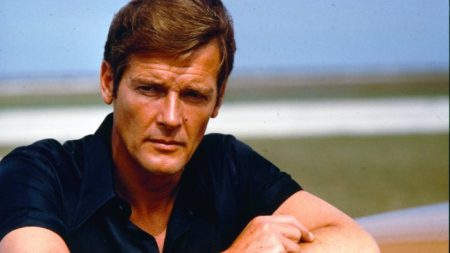

rewrite this title in Arabic Photographer Dawoud Bey: ‘The ground still holds the memory of the slave trail’

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2024 خليجي 247. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.