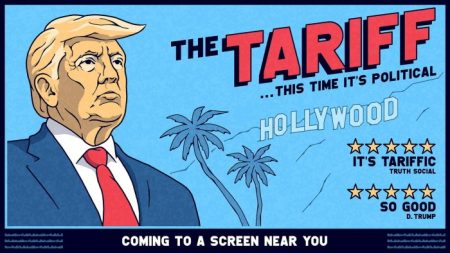

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Over the past 75 years the South Bank has established itself as one of London’s most vibrant art and culture quarters, founded upon its collection of landmark postwar institutions, including the Royal Festival Hall and the National Theatre. But more recently, the South Bank has begun to assert itself as an enticing place to live, with the arrival of major developments such as Southbank Place and now Bankside Yards, which is just getting under way. The postwar story of the neighbourhood, which I have explored in a new book, was one of London’s greatest success stories in terms of urban renewal. The question now is: can the story of the South Bank move on to such acclaim? With their County of London Plan, urban planners Patrick Abercrombie and J.H. Forshaw first marked out the South Bank as a prime site for a new cultural campus, with its collection of “people’s palaces”, back in 1943. They saw that this bomb-damaged area was exceptionally well connected, being a short walk from The Strand or Covent Garden just across the Thames, and close to major rail and Tube stations, as well as being well-served by the river itself. It was also conveniently located next to County Hall, the offices of the old London County Council (LCC), whose politicians, planners and architects would play an important part in the evolution of the South Bank over the coming decades. Fortunately for the South Bank, the idea of a new cultural campus coincided with a grand plan for a Festival of Britain in 1951, a national celebration of British identity and postwar revival. The Royal Festival Hall — designed by LCC architects Leslie Martin, Robert Matthew and their team — formed the one permanent and enduring legacy of the extraordinary South Bank Exhibition, and the following 25 years saw the South Bank turn into a microcosm encapsulating the evolution of Britain’s mid-century modern architecture, charting the rise of brutalism, as seen in the Hayward Gallery, Queen Elizabeth Hall and — eventually — Denys Lasdun’s National Theatre, which opened in 1976. It was a long and fascinating journey.There are some contentious new developments here that underline the sensitivities around the evolution of the setting. Chief among them is the redevelopment of the old LWT and ITV Studios complex by Make Architects, now known as 72 Upper Ground, which could see two new office towers, the tallest 26 storeys high, sitting on a prominent site overlooking — and dwarfing — the National Theatre, as well as Lasdun’s listed IBM Building, which is currently being upgraded. Critics of the scheme, which was approved earlier this year but is subject to an upcoming judicial review, want to see any new design “protect and enhance rather than dominate its surroundings”. The new tower blocks “would overshadow London’s favourite passeggiata,” argues Michael Ball from the Save our South Bank action group. The 20th Century Society’s Coco Whittaker adds that the organisation has no issues with the principle of redeveloping the site but that it “strongly disapprove[s] of the approach adopted in the consented development”, including concerns related to its “scale and massing” on the riverfront. But projects such as the Southbank Place development, which is nearing completion, have proved less controversial in their mission to introduce much needed homes into the area. A master plan by Squire & Partners adds office space and around 880 new apartments — of which 98 will be available at “intermediate” rent, 70 will be “affordable” homes and 19 will be private homes for sale by Lambeth Council — across multiple new buildings alongside the Shell Centre. The seven new towers have been designed by a collective that also includes Patel Taylor, Stanton Williams, GRID Architects and interior architects Johnson Naylor. One reason for this might be that the new mixed-use schemes “build upon the regeneration that the Festival of Britain ignited,” as architect Tim Gledstone, partner at Squire promises. Fewer heritage considerations and constraints on the site, he says, “allows for the emergence of a new London vernacular with international ambition”. The new towers of Southbank Place sit between the listed mid-century icons upon the riverside and Waterloo Station, and arguably help to tie the neighbourhood together. They also bring a new sense of character to the South Bank’s previously unloved hinterland. The Festival of Britain and the people’s palaces along the river have been a key influence. GRID referenced graphic designer Abram Games’ famous Festival Star — as seen on the 1951 Exhibition catalogue and elsewhere — in the design of the facades for the Belvedere Gardens residential towers at Southbank Place. Meanwhile, Fiona Naylor at Johnson Naylor found multiple sources of local inspiration, including the spiral staircases of the Southbank Centre, the influence of which can be seen in her stairs leading from the lobby to the residents lounge at Southbank Place. Naylor has form in the area. She collaborated with Kohn Pedersen Fox on the interiors of the nearby Southbank Tower, an imaginative conversion, extension and retrofit of mid-century architect Richard Seifert’s King’s Reach Tower office block, which marked the beginning of the fresh injection of residential space into the neighbourhood when it was completed back in 2016. The Bankside Yards development further along the river, which will be mixed use, including apartments and a new Mandarin Oriental hotel, promises to anchor itself in the local design language too. As well as repurposing many of the area’s railway arches at street level, Bankside Yards will offer eight new buildings, four of which will be residential. Working to a master plan by PLP Architecture, the architectural team here includes Stiff + Trevillion, Gillespies and Make. The first residential building will be the 50-storey Opus, designed by PLP, which will be the tallest residential building in central London upon completion in 2026, sitting within a cluster of taller structures that have grown up around the junction of the South Bank and Bankside. “Its form tapers as it rises upward . . . and the tripartite plan allows us to create as many as seven corner units on a single floor, which are spatially different and have floor-to-ceiling windows,” says architect and founding partner of PLP, Lee Polisano, of Opus. He “I feel this is just the beginning of the South Bank as a neighbourhood, but its success will depend on . . . creating truly mixed-use communities.” A new chapter is being written for the South Bank, with many twists and turns, as the battle over 72 Upper Ground suggests. It’s a delicate balancing act: protecting the mid-century history, while reinvigorating the area with fresh homes — and combining retrofits with new additions. The end result needs to preserve the essential character of this unique enclave, which has — slowly but surely — won the hearts of so many Londoners.South Bank: Architecture & Design, by Dominic Bradbury & Rachael Smith, will be published by Batsford later this monthFind out about our latest stories first — follow @ft_houseandhome on Instagram

rewrite this title in Arabic Can London make itself at home on the South Bank?

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 خليجي 247. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.