Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Unlock the Editor’s Digest for freeRoula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.As daily life grows increasingly virtual and sedentary, there has been a reactionary pull towards the tactile, active pleasures of age-old crafts. And publishers have taken note. Before the pandemic, non-fiction bestsellers such as Norwegian Wood by novelist and log connoisseur Lars Mytting and Fewer, Better Things by Glenn Adamson, the former director of the Museum of Arts and Design in New York, were already championing the handmade and sustainably utilitarian. The trend was further embedded by the rise of lockdown hobbyists. Now two personable memoirs by British authors amplify that call back to potter’s wheels and sawdust-strewn lathes.In the opening pages of Ingrained: The Making of a Craftsman, we find forty-something Scottish woodsman Callum Robinson running a workshop near Edinburgh that crafts high-end indulgences for commercial clients out of “lustrous platinum blonde” sycamore and toffee-coloured elm. “No one really needs the things we make,” he writes. “The handcrafted whisky cabinet, the elegant picnic trunk for the supercar’s boot, the elaborately carved credenza for the flatscreen TV, there’s no denying that these are all luxuries.”Joining him in this modest venture is his wife, Marisa, a designer who provides the commercial nous, and a motley crew of three young woodworkers who drown out their power saws with rafter-shaking hip hop.When a client pulls a big contract at the last minute, Robinson realises he has put all his planks in one basket. With the business suddenly in peril, he pivots: the couple open a shop in the prosperous market town of Linlithgow and begin making cabinets, tables, desks and kitchen utensils for passing trade.While economically risky, the shift to making items for everyday use has a profound effect, triggering recollections of learning his craft from his father, a landscape gardener turned master woodcarver. Robinson’s prose is humorous and macho, taking its lead from the gruff, sensual delivery of food writer Anthony Bourdain. This is woodworking as a man’s world: something dry and resinous in Robinson’s stove catches “with a report like musketry”, a Swedish hatchet is “pure axe porn”.There are some whimsical character sketches. Ben, the owner of a sawmill hidden in the local woods, is “a Quentin Blake illustration with a chainsaw,” while the preppy landlord of his high street shop is “a man whose shoulders are screaming out for a sweater”. But wood, in all its facets, remains at the heart of his writing. Robinson is poetic about the pageant of ash, beech and pine but also pragmatic: “You are essentially always dealing with very old slices of dried plants.”In Clay: A Human History, Jennifer Lucy Allan brings a journalistic eye to a messier, more mercurial material. Not content with simply surveying centuries of moulding, throwing and glazing, she gets stuck into the sticky stuff herself, learning first how to pinch a pot — “like most terrible pots, it has a rustic charm when planted up with a cactus” — before progressing through a series of more difficult techniques. “I have thrown the crockery that I now eat off,” she notes with pride.“Clay is earth locked in a cycle with water and air that is only broken when we surrender it to fire,” writes Allan, noting that clays are categorised according to the temperature at which they fire. She corrals the views of architects, artists, musicians, geologists and even a witch to unpick this complex human intervention, one that blends science, imagination and pure chance.Her sources range from the well-known — celebrated potter-artist Edmund de Waal dismisses the Fonthill Vase, an important example of Chinese porcelain, as a “flummery of ideas” — to lesser-known figures such as the Yorkshire artist Jade Montserrat, who created a video work in which she rolls around “naked in a muddy hole, kneading and dragging the clay over her body”. In her previous book The Foghorn’s Lament (2021), Allan studied an array of coastal soundscapes — the author has a PhD in foghorns — and here she addresses how porcelain has long been defined by the pitch of its bell-like ring when struck. The book applauds flaws. Allan details the Japanese practice of kintsugi, a technique for repairing broken ceramics, “in which resin, glue or lacquer is used to fix the object back together, and then decorated in gold or silver”. She loves how kintsugi gives value to a fault, how it celebrates the break. Similarly, in his book, Robinson rhapsodises about the “gnarled cracks and the swirling tumultuous grain, the tension and the scars” in an old panel of oak.These two charming and informed volumes deliver the message that working with a natural material brings an ego-free thrill. As Allan writes, “some people make incredible work, others are still learning, but everyone is making, and everyone wishes they had more time to make.”Ingrained: The Making of a Craftsman by Callum Robinson Doubleday £22, 320 pages Clay: A Human History by Jennifer Lucy Allan White Rabbit £20, 320 pagesJoin our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen

rewrite this title in Arabic Craft works: the joy of manipulating natural materials

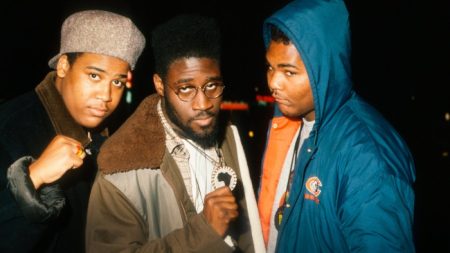

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

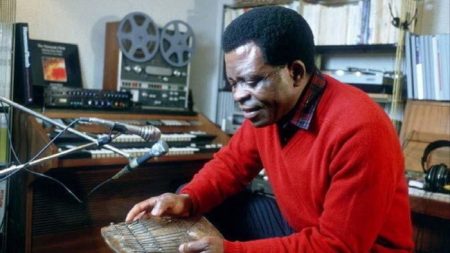

© 2025 خليجي 247. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.