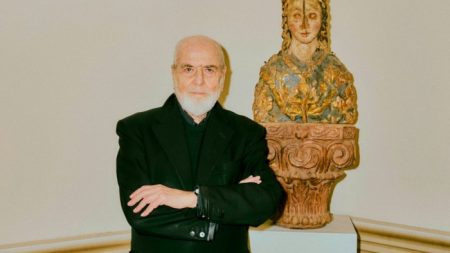

Summarize this content to 2000 words in 6 paragraphs in Arabic Will Gregory is standing in the kitchen of his spacious house in the Somerset countryside, playing a synthesiser frankensteined together from four standard-size breadboards. The instrument, pimpled with inputs and dials, was custom-made for Gregory by “vintage synth specialist” Dani Wilson, whose clients also include Aphex Twin. “It’s a one-off,” beams Gregory, 64, from under a thick mop of hair, initiating a noise that lands somewhere between a deflating balloon and a whale choking on a subwoofer. This is not Gregory’s primary residence — he spends most of his time in Bath with his family — and it’s one of many rewards from his partnership with Alison Goldfrapp, titled after her surname, which brought them hit singles, Grammy nominations and a million-selling album. He bought the house in 2005, the same year they released their breakthrough album, Supernature. Gregory immediately started filling it with rare analogue synthesisers and other vintage equipment. He now has more than 100 synths. They are scattered across almost every conceivable surface, some covered by his wife’s handmade cosies to keep the dust off, others draped with towels. For almost 20 years, alongside his work with Goldfrapp, Gregory has headed his own Moog Ensemble, formed as a homage to the work of Wendy Carlos. Gregory remembers first hearing Carlos’s 1968 hit album, Switched-On Bach, which showed that synthesisers could be used as instruments in their own right rather than merely creating sci-fi noises. “You could hear all the separate parts,” Gregory says of Carlos’s album. “There’s something about the homogeneousness of Brandenburg No 3 on strings which means you don’t get all the detail . . . but when Carlos took it, Bach became really three-dimensional.”In October, the Will Gregory Moog Ensemble (which also features Adrian Utley from Portishead) will perform at London’s Barbican with the Britten Sinfonia. The first half of the show will focus on “synthy, sci-fi movie soundtracks”, with tributes to Carlos and Delia Derbyshire of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop; the second half will present the London premiere of Gregory’s new Archimedes Suite, derived from his recent concept album Heat Ray, which was inspired by the work of the ancient Greek mathematician and physicist.Gregory spent the Covid lockdown educating himself about maths, scouring YouTube for lectures by physicists Richard Feynman and Sidney Coleman. He became infected by their love of Archimedes, a man who, according to legend, conceived of a death ray that would use mirrors and polished metal to burn incoming ships. “I had this idea,” Gregory says, “that maybe we could do a The Planets-style concert but instead of going through the planets we go through Archimedes’ theorems, [with] a Peter and the Wolf explanation between them.” Thus the Barbican show will feature Gregory’s spoken introductions and insights between sections. The music itself features spirals and patterns inspired by Archimedes’ work.We move into Gregory’s studio, which is bathed in the glow of afternoon light from a wall-length window. The room is stacked with machinery. There’s a Hohner Clavinet model C, best known for its bassline on Stevie Wonder’s “Superstition”, a rare instrument called a Swarmatron and an Audix mixing desk assembled from second world war submarine parts. Gregory insists that he’s not a collector; it’s “all about the sound and how they perform”. The synthesiser is a strange, almost paradoxical instrument. It helped shape a futuristic tonal landscape in an era that looked forward to Moon bases and flying cars. In this way, the synthesiser emits the memory of a future that never arrived. Moreover, the past half-century of popular music has been marked by technical innovations: the synth, the drum machine, the sampler, the sequencer. But cultural theorists such as Mark Fisher have argued that the rate of these innovations has slowed, or shifted from the production to the marketing and consumption of music.“I think that happens every generation,” Gregory counters. “In the 1900s they said there’s nothing more we can learn about physics; it’s all been worked out. I think there will be a new generation that will redefine what commercial music is or what is acceptable music or what is listenable. I’m starting to hear, in a lot of hip-hop, that trad four-to-the-floor aspect of commercial music disappearing. So I think the first set of innovations are going to be rhythmic.” We turn to Goldfrapp, the two-decade-long partnership that reminded Gregory of being “a kid in the sandpit” and reshaped his approach to music. “[Alison] is supersensitive to all aspects; things would be annoying to her which weren’t annoying to me, but I would go, ‘Oh OK, yeah, we should sort that out.’ It’s helped me be self-critical.” They are very different people. Whereas Alison is extrovert on stage, Gregory seems extremely comfortable in the studio and, as of Goldfrapp’s second album, almost never played live with the group. Instead he’d be watching backstage or at the mixing desk with the front-of-house sound engineer.“I just thought [playing live] was unnecessary. The music was written with the voice right in the centre, and to that end it didn’t matter who was on stage with Alison.” Both the founding members of Goldfrapp were in their late thirties when the band was formed, Alison having honed her skills working with artists such as Tricky. Gregory trained as an oboist, then took up saxophone at the age of 20 and moved to the US where he played dive bars in Berkeley, California. When he got back in 1983, he was excited to find that almost every cool band wanted a sax player. After touring with Tears for Fears, Gregory went on to play with Peter Gabriel, The Cure and Portishead. “To break through you need to make all the right decisions and then you have to not believe the hype. By the time I came to be working with Alison, that level of maturity was where I needed to be.” In the end, there wasn’t a break-up so much as a drifting apart. During the pandemic they tried to work remotely but couldn’t do it. Both began pursuing their own projects. Alison’s debut solo album, The Love Invention, came out last year and Gregory started on Heat Ray, alongside composition for film and television (he has a number of film score credits, including for Sam Taylor-Johnson’s Nowhere Boy). Despite this, Gregory says he’s not interested in working with other singers: “I don’t think there’s anybody else that I want to work with.” When I push him on whether he thinks we might see a new Goldfrapp record, he seems wistfully hopeful. “We might get back together and do stuff . . . We’re both open to the idea of working together again, but after seven records it feels like it’s good to have a natural break.” Before I leave, Gregory shows me another piece of kit, an Oberheim Two Voice, which he’s particularly proud of. He presses a key and out comes the sound of a cash register, tied to a skateboard, being dragged across a frozen lake. I ask whether this couldn’t just all be digitised and Gregory answers with perhaps the most essential defence of analogue equipment anyone can give: “I’m not against softsynths in Logic [computer programmes that create digital audio], but what they haven’t got is knobs.”Will Gregory Moog Ensemble with the Britten Sinfonia, Barbican, October 8, barbican.org.uk

رائح الآن

rewrite this title in Arabic Will Gregory: in love with the sound of synths

مقالات ذات صلة

مال واعمال

مواضيع رائجة

النشرة البريدية

اشترك للحصول على اخر الأخبار لحظة بلحظة الى بريدك الإلكتروني.

© 2025 خليجي 247. جميع الحقوق محفوظة.